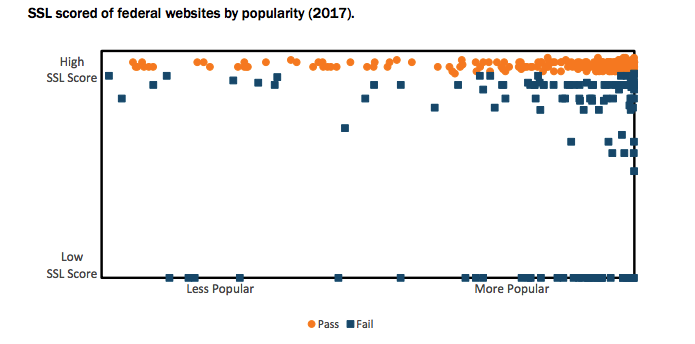

Only 71% of Government Websites Pass the SSL Test

DNSSEC is becoming more widely enabled, but SSL best practices continue to lack.

On Monday, the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation released a report titled, “Benchmarking U.S. Government Websites.” 90 pages, chock full of interesting statistics about the performance and security of the federal government’s myriad websites.

One of the most interesting takeaways from the report is that SSL adoption continues to grow among government websites, but it’s not necessarily being implemented properly. Or in other words, there is still much work to be done!

Let’s Hash it Out.

While I definitely recommend looking through the report for yourself, I also realize 90 pages is a lot. So we’ll stick to the SSL-related bits, starting with the study’s methodology. Basically, they identified a list of 468 federal government websites and tested each one against four benchmarks. For our purposes, three of those benchmarks mean very little, we’re mostly focused on security.

To measure federal websites’ compliance with these standards, the report uses two different publicly available tools. First, we used the Verisign Labs’ “DNSSEC Debugger,” a web-based tool that inspects websites for DNSSEC, testing that digital certificates are verified in a “chain of trust” for each federal website’s domain…

Second, to identify whether websites enable HTTPS, we used a tool that checks Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) certificates, which underpin most HTTPS connections. Qualys SSL Labs’ “SSL Server Test” inspects public SSL web servers based on four criteria: certificate, protocol support, key strength, and cipher strength. The tool also analyzes websites for several other factors that would be detrimental to its security, such as outdated protocols or security vulnerabilities. Using the numerical value of the tool’s four criteria and weighting these scores based on whether the tool detected major issues with a website’s security (e.g., a known security vulnerability), we produced a final SSL score for each website between 0 and 100 points. If “SSL Server Test” failed to detect an SSL certificate or resulted in an error for a specific website, we used the Chrome web browser to determine whether the website used HTTPS, adjusting the website’s SSL score to reflect whether it used HTTPS.

A score of 90 was deemed passing.

Here are the biggest takeaways:

- 90% of the websites reviewed had enabled DNSSEC.

- Only 71% of the reviewed websites passed the SSL test this year.

- That’s a small upward tick, up from 67% last year.

- However, of the Government websites appearing the Alexa 100,000, the number of passes fell from 78% to 75%.

- The majority (55%) of the websites tested in both this year’s report and last’s did not improve or decline.

- 31% of the websites tested improved their SSL score, 14% declined

- Of the websites that did not change one way or another, 23% failed the SSL test.

Additional Insights about SSL and the Federal Government

Here are a few other tidbits worth highlighting from the report:

- All but 8% of the websites reviewed had HTTPS enabled

- The International Trade Administration (trade.gov) is still served via HTTP

- The US Trade Representative (ustr.gov) and the National Weather Service (weather.com) are both vulnerable to the POODLE attack

- The International Trade Administration (trade.gov) is vulnerable to DROWN.

Another large problem was misconfiguration and support for outdated ciphers.

In addition to major security flaws, many federal websites failed the SSL test due to other security issues, such as the lack of perfect forward secrecy and outdated cryptographic algorithms… Some federal websites also use cryptographic standards that have not been updated to eliminate vulnerabilities, such as Rivest Cipher 4 (RC4) … or weak Diffie-Hellman key exchange parameters—a popular cryptographic algorithm that allows a web browser and server to negotiate secure connections.

A Final Word

One of the reasons that we support shorter certificate lifespans is that by constantly having to issue and install new certificates, you’re keeping your encryption more up to date. On the flipside, the longer you have a digital certificate just sitting there on your server, the more outmoded it becomes.

You need to be updating your implementations regularly to ensure support for the latest protocols, ciphers and algorithms. Some of the vulnerabilities disclosed in the report are caused by support for deprecated older SSL versions like SSL 3.0. To give you a sense of scale, it’s not technically even called SSL anymore. It’s now Transport Layer Security (TLS) and we’re on protocol 1.3. If you’d like to learn more about ciphers and algorithms, you can find it here, but suffice it to say you always want to make sure you’re supporting the newest, most secure ciphers and deprecating support for older, outmoded ones.

The point is there’s more to securing your website than simply adding SSL. Whether it’s adding an HSTS header or making sure your site only supports the safest cipher suites, there’s a difference between just having SSL and using it to its potential.

![A Look at 30 Key Cyber Crime Statistics [2023 Data Update]](https://www.thesslstore.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/cyber-crime-statistics-feature2-75x94.jpg)

5 Ways to Determine if a Website is Fake, Fraudulent, or a Scam – 2018

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityHow to Fix ‘ERR_SSL_PROTOCOL_ERROR’ on Google Chrome

in Everything EncryptionRe-Hashed: How to Fix SSL Connection Errors on Android Phones

in Everything EncryptionCloud Security: 5 Serious Emerging Cloud Computing Threats to Avoid

in ssl certificatesThis is what happens when your SSL certificate expires

in Everything EncryptionRe-Hashed: Troubleshoot Firefox’s “Performing TLS Handshake” Message

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityReport it Right: AMCA got hacked – Not Quest and LabCorp

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityRe-Hashed: How to clear HSTS settings in Chrome and Firefox

in Everything EncryptionRe-Hashed: The Difference Between SHA-1, SHA-2 and SHA-256 Hash Algorithms

in Everything EncryptionThe Difference Between Root Certificates and Intermediate Certificates

in Everything EncryptionThe difference between Encryption, Hashing and Salting

in Everything EncryptionRe-Hashed: How To Disable Firefox Insecure Password Warnings

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityCipher Suites: Ciphers, Algorithms and Negotiating Security Settings

in Everything EncryptionThe Ultimate Hacker Movies List for December 2020

in Hashing Out Cyber Security Monthly DigestAnatomy of a Scam: Work from home for Amazon

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityThe Top 9 Cyber Security Threats That Will Ruin Your Day

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityHow strong is 256-bit Encryption?

in Everything EncryptionRe-Hashed: How to Trust Manually Installed Root Certificates in iOS 10.3

in Everything EncryptionHow to View SSL Certificate Details in Chrome 56

in Industry LowdownPayPal Phishing Certificates Far More Prevalent Than Previously Thought

in Industry Lowdown