Google’s $80-billion Conflict of Interest

When it comes to HTTPS and Google, there’s a lot more at stake than just your safety

Google is making a hard push towards universal encryption in 2017. In truth, it’s the browser community, but Google is the ringleader and tends to come off as an activist in this regard.

And on its face, that’s fantastic. Heaven knows that we at The SSL Store™, an SSL reseller, favor a fully-encrypted internet. But right now, there’s a massive split between the Certificate Authorities and the browsers, specifically Google, on how that should look. Good points are being made by both sides. But, part of the issue is that only one party has been open about its conflict of interest.

Two Use Cases for Encryption

When we talk about encryption, there are two specific use cases we’re specifically referring to as it relates to users. Melih Abdulhayoglu, the CEO of Comodo, wrote about this in April.

The first use case is “Encrypting Against”

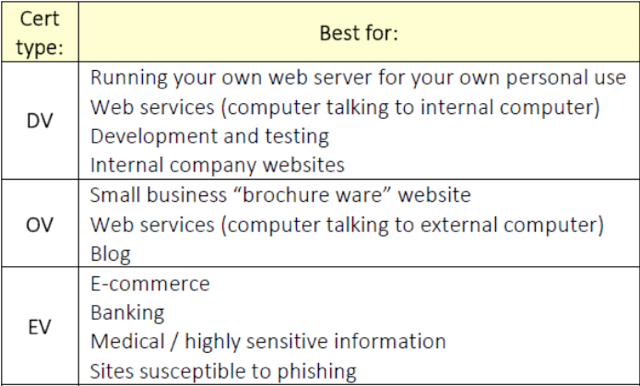

Melih calls this “Encrypting to Avoid,” we call it “Encrypting Against.” Either way, in this instance, encryption is used to “encrypt against” eavesdropping, MITM and content injection. This is what the basic Domain Validation SSL model covers. At the DV level you’re not concerned with who you’re issuing to or what they’re doing, you’re only concerned about encryption for the sake of data privacy and integrity for the domain owner requesting it.

The second use case is “Encrypting For”

In this instance, you’re encrypting sensitive information expressly FOR the purpose of safely transmitting it to an intended or authorized party. In today’s SSL environment, this is the use case for Organization Validation or Extended Validation certificates, where the party on the other end of the connection has been verified as a genuine entity and the actual data in transit is what you’re specifically concerned with securing so that no one other than the intended/authorized party receives it.

At the center of this encryption debate is one question: do you believe encryption should be linked with business identity verification? Or should these be done separately?

Where you stand on that issue dictates which use case you favor.

Google Supports “Encrypting Against”

Google, led by a team of very talented engineers, has been slowly putting its vision into place. It’s been pushing the web towards encryption since it announced SSL as an SEO ranking signal back in 2014. Lately, it is also leading a browser-wide initiative to revamp UI as it relates to connection security.

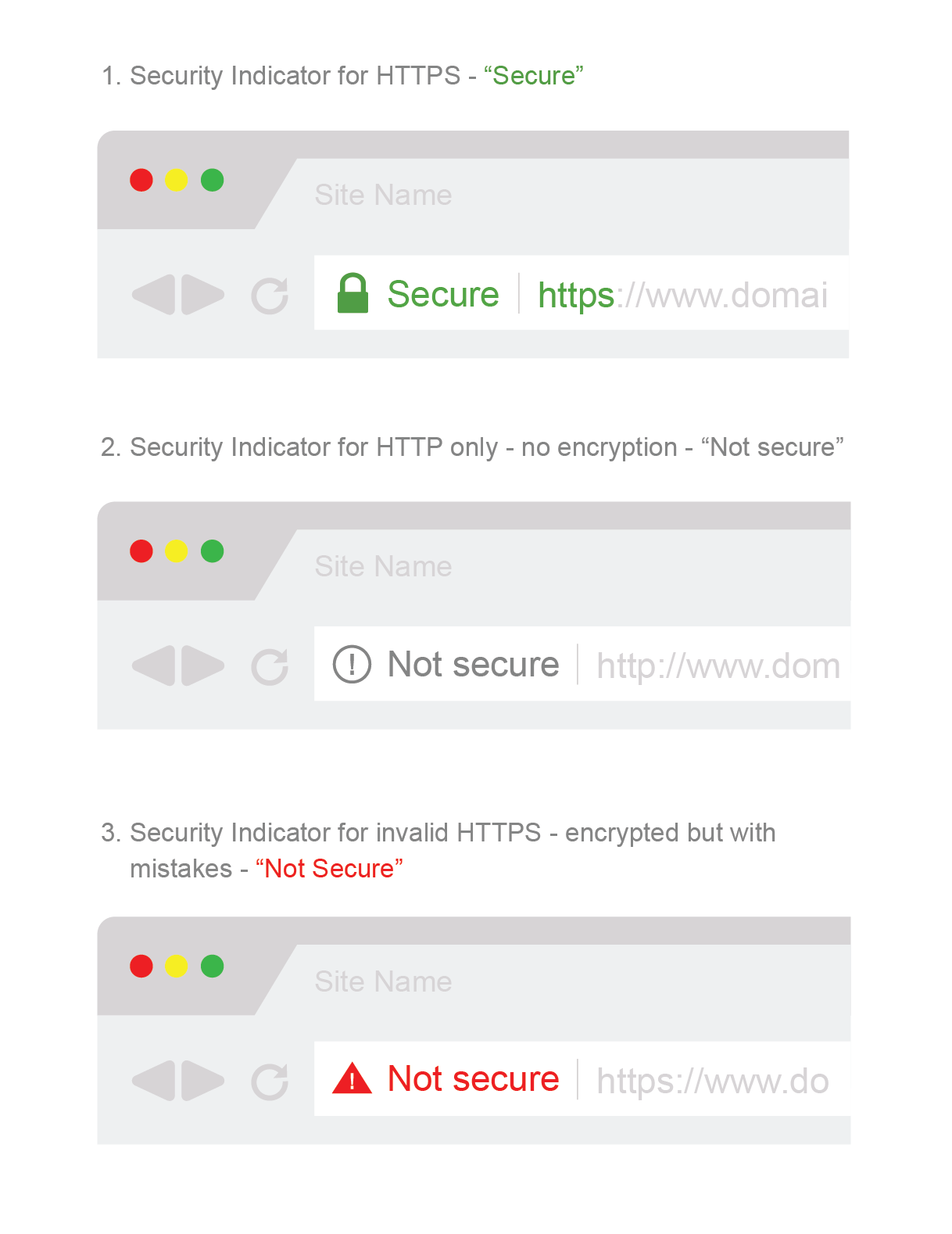

In layman’s terms, Google is phasing out the old indicators in favor of a new binary that labels websites either “Secure” or “Not Secure” based on whether they have basic encryption (DV SSL). This UI change has been made to accelerate the adoption of encryption. And it’s working.

This supports the “Encrypt Against” use case. The way Google views what an encrypted internet should be is: you either have encryption, and your connection is “Secure,” or you don’t and you’re “Not Secure.” Business-level identity authentication is not a consideration. Neither is the fact that, given current precedents and years of miseducation, many internet users mistakenly confuse “Secure” for “Safe.”

The Certificate Authorities Support “Encrypting For”

On the other end of the spectrum the CAs have created an initiative through the CA Security Council that includes a petition for a public endorsement of website identity principles. There are three principles in total:

- Website identity is important for user security.

- TLS certificate types that are used to secure websites – Extended Validation (EV), Organization Validated (OV), and Domain Validated (DV) certificates – should each receive a distinct, clearly-defined browser UI security indicator showing users when a website’s identity has been independently confirmed.

- Browsers should adopt a common set of browser UI security indicators for each certificate type, and should educate users on what the differences are to promote user security.

This is an example of “Encrypting For.” The CAs acknowledge there is a place for DV certificates, but favor higher authentication certificates that leverage identity and offer more assurance to users as to who is on the other end of a secured connection.

In Kirk Hall’s RSA 2017 presentation, he defined use types for each level of SSL certificate:

While the Certificate Authorities also want a fully encrypted internet, their vision involves business-level identity authentication and a better revocation system to combat the push for shorter certificate times. Whereas Google wants to turn encryption into a Secure/Not Secure binary, the CAs favor a model that distinguishes between levels of authentication to provide greater user assurance.

This, of course, all comes with one HUGE caveat.

The Certificate Authorities Have a Financial Interest in SSL

Unfortunately, for many involved in the debate over SSL, this is a point of contention: CAs are businesses, they are trying to make money.

It’s true.

It’s also true that the influx of free SSL services over the past couple of years has been a disruptive force in the SSL ecosystem. We’re shooting straight from the hip here, the new players in the DV market have caused many CAs to double down on their higher authentication SSL products.

And no, free DV certs aren’t putting anyone out of business. They’re not an existential threat to the CAs as so many around the internet community are quick to exclaim. In fact, with the rush to encrypt, business is actually booming.

Where this debate begins to go off the rails is here: there’s nothing wrong with being a business. SSL certificates provide a value both in the form of encryption and identity authentication. There’s room for both free SSL services and commercial Certificate Authorities in the ecosystem.

But there’s also a double-standard at play here too. The CAs are forced to admit to, and are constantly reminded of their conflicts of interest—that they have a financial stake here. That they’re businesses.

But, Google has a massive conflict of interest in this debate, too. Google is also a business. That’s a fact that a lot of people involved in this discussion fail to point out.

Google Has an $80,000,000,000 Conflict of Interest

Google as a brand is aspirational. It’s a great American company. In many ways, it’s understandable that people forget that Google is also a mega-corporation. It’s not altruistic. It’s in it for itself.

On its HTTPS Transparency page, Google says that encryption “thwarts interception of your information and ensures the integrity of information that you send and receive.”

That feels good. It’s well written. It sounds like Google’s really looking after you.

And they are, but that’s just a pleasant side effect of Google looking after itself. As we discussed, Google favors the “Encrypt Against” use case—its behavior backs this up 100%. And in the “Encrypt Against” model, you’re encrypting to prevent a specific party from seeing your traffic. From injecting things.

You’re encrypting to protect Google’s ad revenues

Every time you see a major news outlet migrate to HTTPS – be it Wired, the Guardian or the New York Times – one of the reasons is always to prevent their own ads from getting blocked at the ISP level. Yes, Internet Service Providers currently cut into a website’s ad revenues by way of content injection when a website is served over an HTTP connection. The website is providing the valuable ad real estate, but it’s no longer making money from it. Neither is the ad network they partnered with.

That’s one of the lesser advertised features of SSL: it blocks third-party content injection by obfuscating what the client is viewing. An HTTPS connection prevents ISPs from injecting their ads.

Have you ever noticed when you use the Wi-Fi at a Starbucks or on an airplane you see an influx of ads that wouldn’t normally be there? That’s third-party content injection (Vince wrote a great piece about this last year). When that occurs, the ISP – not the website displaying the ad – makes money.

If your business relies on ad revenues, this can be a gigantic problem. Now, quickly, which Ad Networks have the largest market share?

Google’s! Google’s total market share is almost 63%! Last year Google did 79.38 BILLION (with a B) dollars in ad revenue. To provide greater context, Google, as a whole, did 89.46 billion dollars in revenue in 2016. That means ad revenue accounts for 88.7% of its revenues. And Google accounts for 99% of its parent company, Alphabet’s revenues.

So, when Google says encryption ensures the integrity of information that you send or receive, it’s more interested in the latter half of that equation—what you receive. As in, its ads. As they were intended. And not with an ISP scraping off the top.

Encrypting is Just Step One

Google also plans to roll out its own ad blocker in Chrome next year (conveniently after Google’s target date for complete encryption). Google’s ad blocker will be set as a default on the Chrome browser – which is used by more than half of all American internet users – meaning most users won’t even know it’s filtering.

And what ads will it filter?

“The ones not sold by Google, for the most part.”

Google will be using the standards set forth by the Coalition for Better Ads. Which sounds great, and definitely gives you the impression that Google is looking out for its users—after all, everyone hates ads.

But the Coalition for Better Ads is not without its critics. Mark Patterson, a Fordham University law professor who specializes in antitrust law, patent law, internet law, and contracts, has called the coalition a “cartel” that has been orchestrated by Google.

Once again, the fact that Google’s users may benefit from this is really just a pleasant side effect of Google’s own self-interest.

Google Isn’t the Bad Guy

Now, the point here isn’t to bash Google. It’s OK to be a business. It’s OK to protect your own interests.

There’s absolutely nothing wrong with that.

The point of this exercise was just to reset the discussion. Google is not acting on behalf of the internet’s best interests to stand against big business imposing its will. Google IS big business imposing its will. This debate is Big Business vs. Big Business. There is no altruism in this discussion, just dollars and cents.

Let’s keep that in mind as we propose a set of solutions that we think will both help the rapid proliferation of encryption, while also adding a much-needed layer of security in the form of stronger authentication practices.

What We Propose

We, at The SSL Store™ have no problem with Google protecting its own business interests. The company is uniquely positioned to do so and failure to act on it would be a disservice to the company itself and its shareholders.

We get that.

But there is room for both sides to get what they want. For Google to have the vast majority of the internet encrypted against content injection, while leaning on websites that deal in sensitive information to authenticate themselves. These goals can both be accomplished.

Here’s what we propose:

- Strengthen and agree upon the standards for validation on both Organization Validation and Extended Validation SSL certificates. The browsers have voiced that they don’t feel that the standards for either OV or EV are stringent enough. That’s fair. But rather than simply objecting, let’s work together to solidify the standards.

- Eliminate the current encryption binary. As it is worded, these visual indicators are misleading to a good percentage of the public. Assuming people will educate themselves is naïve. We need a system that better indicates both connection security and the level of authentication.

- Visual Indicators should be agreed upon by both the browsers and the CAs, and made uniform across all the browsers. A uniform UI will help give users a better understanding of connection security while ensuring that authentication is represented in terms of degree.

- Either create a DNS-based revocation platform that allows the browsers to perform Hard Fails. Otherwise, certificate validity periods should be shortened to a year. Given the lack of a reliable revocation system and the need to quickly proliferate advances in encryption technology, this seems like an ideal length.

These problems are solvable. Even though each company and organization involved has its own agenda, there is a way to build consensus and reach an outcome that satisfies all parties—including users.

We would be remiss not to work towards that outcome.

![A Look at 30 Key Cyber Crime Statistics [2023 Data Update]](https://www.thesslstore.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/cyber-crime-statistics-feature2-75x94.jpg)

5 Ways to Determine if a Website is Fake, Fraudulent, or a Scam – 2018

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityHow to Fix ‘ERR_SSL_PROTOCOL_ERROR’ on Google Chrome

in Everything EncryptionRe-Hashed: How to Fix SSL Connection Errors on Android Phones

in Everything EncryptionCloud Security: 5 Serious Emerging Cloud Computing Threats to Avoid

in ssl certificatesThis is what happens when your SSL certificate expires

in Everything EncryptionRe-Hashed: Troubleshoot Firefox’s “Performing TLS Handshake” Message

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityReport it Right: AMCA got hacked – Not Quest and LabCorp

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityRe-Hashed: How to clear HSTS settings in Chrome and Firefox

in Everything EncryptionRe-Hashed: The Difference Between SHA-1, SHA-2 and SHA-256 Hash Algorithms

in Everything EncryptionThe Difference Between Root Certificates and Intermediate Certificates

in Everything EncryptionThe difference between Encryption, Hashing and Salting

in Everything EncryptionRe-Hashed: How To Disable Firefox Insecure Password Warnings

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityCipher Suites: Ciphers, Algorithms and Negotiating Security Settings

in Everything EncryptionThe Ultimate Hacker Movies List for December 2020

in Hashing Out Cyber Security Monthly DigestAnatomy of a Scam: Work from home for Amazon

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityThe Top 9 Cyber Security Threats That Will Ruin Your Day

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityHow strong is 256-bit Encryption?

in Everything EncryptionRe-Hashed: How to Trust Manually Installed Root Certificates in iOS 10.3

in Everything EncryptionHow to View SSL Certificate Details in Chrome 56

in Industry LowdownPayPal Phishing Certificates Far More Prevalent Than Previously Thought

in Industry Lowdown