Historical Encryption: The Babington Plot

One of the first recorded Man-in-the-Middle attacks literally cost someone their head

Encryption has never been more universal than it is in 2018. Nowadays, as of the last week of July, every website on the internet needs to have an SSL certificate installed so that it can secure connections made with its visitors’ browsers via encryption.

And it’s easy to let yourself think that encryption is a fairly recent invention given that we typically see it used in a digital context. Encryption is what protects our data online. But it’s been protecting data since way before the creation of the internet.

In fact, the first known use of encryption was around 1900 BC when it appeared in the form of non-standard hieroglyphs chiseled into the wall of an ancient tomb. Since then, it’s been used by countless cultures to obfuscate communication from the prying eyes of third parties. Other famous examples include Caesar and Polybius, Al-Kindi, or, more recently, the Enigma machine in World War II.

Today we’re going to look back at an infamous moment in history when encryption failed spectacularly: the Babington Plot.

As you’ll see, it’s not just CIOs and CISOs that can lose their heads when encryption goes bad…

The Babington Plot

Mary Stuart, often called Mary, Queen of Scots became the Queen of Scotland at six days old and remained Queen until she was abducted at 24, imprisoned in a castle and forced to abdicate the throne to her one year-old son. That’s kind of the abridged version, a lot happened over the course of that quarter century: she was betrothed before she could even walk, shipped to France at five to be married by ten for political purposes (though the marriage didn’t occur until she was 15). She also may have had a hand in killing a subsequent husband and probably married the man who actually carried out the deed. I include this information – not because it has a ton of bearing on the rest of this tale – but because it’s interesting in a kind of, “whoa” sort of way.

About a year after being imprisoned and forced to abdicate, Mary escaped and fled to England looking for aid from her first cousin, once removed, Queen Elizabeth I. It wasn’t that simple though. You see, Mary was a legitimate heir to the English throne. In some people’s eyes, she was the rightful heir owing to the fact Elizabeth was an illegitimate child after her parents’ marriage was ruled illegal. Further complicating things, Mary was a Roman Catholic whereas Elizabeth was a protestant. And Pope Pius V had recently issued a formal decree granting English Catholics authority to overthrow Elizabeth.

Mary may have been royalty, but she was also a pawn in a sense. Opportunistic Catholic elements viewed her as a potential vehicle for the overthrow of the English throne, which would open the door for a return to Catholicism for the English.

Sensing the risk Mary posed, Elizabeth imprisoned her for the next 19 years. With the help of Parliament, Elizabeth also passed laws that would see Mary executed if anyone plotted against the queen on her behalf, as well as a law that would allow for the execution of anyone that would benefit from the death of the queen in the event a plot against her is discovered.

Believe it or not, that was the merciful route. Many around Elizabeth wanted Mary dead. One of those people was Sir Francis Walsingham, who was rightfully concerned about the papal threat. Walsingham knew Elizabeth would never have her cousin assassinated unless there was concrete evidence of Mary’s participation in a plot against her life.

So, he decided to enact a plan that would implicate Mary in a coup attempt against Elizabeth. Walsingham served as Elizabeth’s spymaster and hatched a scheme to use a double agents, like Gilbert Gifford and Robert Poley, to entrap Mary, her trusted secretary and confidant, Thomas Morgan and the rest of the conspirators.

Plotting a Coup d’état

History is written by the victor, which can sometimes make it more difficult for historians to tell the exact sequence of events that occurred in the Babington Plot. Part of the issue is that a couple of different conspiracies get lumped into one.

A better way to think of it is that one domino needed to topple before the other one could get knocked down. That first domino was assurance of foreign support for the overthrow of Elizabeth and the return of Catholicism to England. The conspirators were keenly aware that even with Elizabeth out of the way, there would be enough Protestant elements left in England that it would be impossible to achieve control without help from a foreign army. Preferably Spain’s, given its Catholic king.

A Jesuit priest, John Ballard, an agent of the Roman Church had already received support from the Northern Catholic gentry. Gifford helped pass along assurances of support from the Spanish crown.

By this point Walsingham had already arrested Gifford and persuaded him to serve as his double agent. It’s not really clear how willing a participant Gifford actually was. While history tends to have him on the side of Elizabeth and the Protestants, there’s a lot of evidence he truly supported Mary and acted purely out of self-preservation, too. He, himself, was a Catholic. Either way, he played a critical role. Gifford facilitated the transfer of correspondence between Mary and her followers.

While Mary may not have been initially inclined to support an attempt on her cousin’s throne following her flight to England—19 years of captivity is plenty of time to generate a little enmity. By the time Gifford obtained her confidence in 1586, she was a willing participant. Gifford had also ingratiated himself with Anthony Babington, who had served as a courier for Mary before communication with her had been cut off by Elizabeth, and with the French Embassy in London. He was largely responsible for restarting Mary’s correspondence with her supporters and facilitating it in the months that followed.

To circumvent the ban on communication, messages were placed in a watertight casing inside the stoppers of beer barrels delivered to and collected from Chartley Manor, where Mary was being held. To add an additional layer of security, all messages were written in a cipher meant to keep the contents of the message secret should they fall into the wrong hands. Or put another way, they were encrypted.

One of the first recorded Man-in-the-Middle attacks in history

Unbeknownst to the conspirators, Sir Francis Walsingham was intimately aware of the details of what was taking place. In fact, his manipulation was a major reason for why the Babington Plot got as far as it did.

Ballard, the Jesuit priest, was working with a companion and confidant, Barnard Maude, that was secretly in Walsingham’s employ. Likewise, Babington, one of the leaders of the eponymous Babington plot, was actually seeking a passport to France before Robert Poley convinced him there was no hope of obtaining one and pushed him back into leading the plot.

It’s not really clear whether the Babington plot, independent of Walsingham’s influence, would have ever been more than just talk. But with Walsingham pulling strings and egging the conspirators on from behind the scenes, it definitely produced enough evidence to implicate all involved.

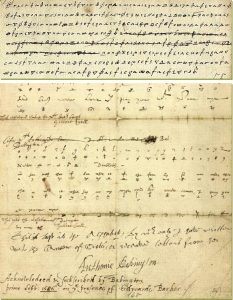

That was thanks to one of the first recorded Man-in-the-Middle attacks in history. Gifford was indeed delivering the messages as he was supposed to, but not before he supplied a copy to Thomas Phellipes, Walsingham’s cryptographer, who decrypted the communication for evidentiary purposes. At one point Phellipes even added a post script to a letter from Mary to Babington, asking that he name his co-conspirators.

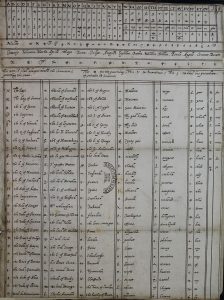

Mary’s cipher was a Nomenclator cipher, a type of substitution cipher that replaces some of the most common words used with symbols. Think about it like this, if you’re running a simple substitution cipher, one that replaces every letter with another, one of the methods for cracking it is to try to identify common words, which will help you map the substitutions. For instance, if you’re encrypting a message to Esteban, chances are you may use his name in the message a few times. If a codebreaker can find the encrypted form of Esteban, it helps them decrypt the rest of the message by helping them to build a key. So to further obfuscate what’s being sent, Nomenclator ciphers replace some of the most common words with their own symbols. Instead of writing out Estaban, now you’ll just write the shorthand symbol instead.

This is a form of Private Key encryption. The private key in this case would be the chart or table that shows the substitution method or algorithm used to encrypt the message. Babington and his co-conspirators did a poor job with key security. As in, Giffords was able to provide Walsingham’s cryptographer, Phellipes, with a copy of the private key.

It took seven months of Phellipes decrypting Mary’s correspondences – which often included very mundane details of her day-to-day life in captivity – before Walsingham finally got what he wanted. In the meantime, he had let a plot against Queen Elizabeth (one that in many ways he facilitated himself) continue to unfold while he waited for the evidence he needed to implicate Mary.

Ultimately, it was five words that doomed her. After speaking mostly in a hypothetical sense and warning that any attempted coup would require foreign support, she gave clear support for the assassination of Elizabeth if it would end her captivity and bring Catholicism back to England.

Then she gave her signal. In the letter that would end her life she wrote:

“Let the great plot commence.”

The aftermath of the Babington Plot

With what he needed to implicate Mary in hand, Walsingham sprung into action. John Ballard, the Jesuit priest was arrested and tortured, which led to him implicating Babington and some of the other conspirators. All in all, they rounded up and condemned 14 men to death.

On September 20th, 1586, Babington, Ballard and five others were hanged, drawn and cornered. Ballard, whose arms and legs had been torn from their sockets and joints on a torture rack, had to be carried to the makeshift gallows that had been erected for the execution. The first day of executions was so horrific and bloody, that Elizabeth ordered that the second set of prisoners be hung to death before the disembowelment and dismemberment commenced.

Mary Stuart, as a royal and the cousin of the Queen, received a trial in a kangaroo court in which she could not review evidence or have counsel. She was found guilty of her role in the Babington Plot by a jury of 36 noblemen, with only a single lord voicing dissent. It was at this trial that Mary discovered her correspondence had not been secure, and that its contents would now be used against her.

Even despite her death sentence, Elizabeth was hesitant to execute her cousin. So, ten members of the Privy Council of England decided to commence with the execution immediately, behind Elizabeth’s back, in February of 1587.

Five days later, Mary would make the walk to the chopping block. And much like everything else involved in the Babington Plot, the execution didn’t go as planned. The executioner, a man known as Bull, missed her neck entirely on the first swing and struck her in the back of the skull. The second swing did the trick and decapitated her—mostly.

After using the axe to cut through the last piece of sinew connecting Mary’s head to her body, he tried to hold it aloft, but failed to realize Mary was wearing a wig, which caused the head to drop and roll on the floor.

Upon hearing of the botched decapitation Elizabeth was so upset she threw the executioner in the Tower of London and imprisoned him there for the next 19 months.

And then they all lived happily ever after. As you do.

Final Thoughts

While the point of this article was to engage you with an interesting historical tale that has some overlap with encryption and data security, there are a couple of decent lesson you can still take from this. What? Don’t laugh.

First of all, this is a (fairly) extreme case of what can happen with a Man-in-the-Middle attack. While you probably won’t wind up getting drawn and quartered as a result of MITM, this does illustrate what kind of damage can be done with such an attack. Walsingham was able to use the data stolen from Mary’s correspondence with the other conspirators to incriminate her and ultimately end her life. He was also able to manipulate the communication, most famously when Phelippes rewrote one of the final letters asking Babington to name his accomplices.

Babington was arrested before he could respond, but had that not occurred he would have had no way of knowing that Mary’s message had been manipulated. That Phelippes, working as a proxy for Walsingham, had literally injected content.

And of course, back then there was no way to authenticate the sender or verify the integrity of the document. I realize that may sound silly, but either one of those modern features probably could have helped. You can also make a point about private key security and how dangerous using a compromised private key can be.

So remember, the next time you’re visiting a website or talking about SSL, the concepts at work here have existed for thousands of years in some form. Our digital world is just the first time a lot of us are seeing them.

And don’t ever let anyone tell you that good encryption isn’t a matter of life and death!

As always, feel free to leave any questions or comments below.

![A Look at 30 Key Cyber Crime Statistics [2023 Data Update]](https://www.thesslstore.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/cyber-crime-statistics-feature2-75x94.jpg)

5 Ways to Determine if a Website is Fake, Fraudulent, or a Scam – 2018

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityHow to Fix ‘ERR_SSL_PROTOCOL_ERROR’ on Google Chrome

in Everything EncryptionRe-Hashed: How to Fix SSL Connection Errors on Android Phones

in Everything EncryptionCloud Security: 5 Serious Emerging Cloud Computing Threats to Avoid

in ssl certificatesThis is what happens when your SSL certificate expires

in Everything EncryptionRe-Hashed: Troubleshoot Firefox’s “Performing TLS Handshake” Message

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityReport it Right: AMCA got hacked – Not Quest and LabCorp

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityRe-Hashed: How to clear HSTS settings in Chrome and Firefox

in Everything EncryptionRe-Hashed: The Difference Between SHA-1, SHA-2 and SHA-256 Hash Algorithms

in Everything EncryptionThe Difference Between Root Certificates and Intermediate Certificates

in Everything EncryptionThe difference between Encryption, Hashing and Salting

in Everything EncryptionRe-Hashed: How To Disable Firefox Insecure Password Warnings

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityCipher Suites: Ciphers, Algorithms and Negotiating Security Settings

in Everything EncryptionThe Ultimate Hacker Movies List for December 2020

in Hashing Out Cyber Security Monthly DigestAnatomy of a Scam: Work from home for Amazon

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityThe Top 9 Cyber Security Threats That Will Ruin Your Day

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityHow strong is 256-bit Encryption?

in Everything EncryptionRe-Hashed: How to Trust Manually Installed Root Certificates in iOS 10.3

in Everything EncryptionHow to View SSL Certificate Details in Chrome 56

in Industry LowdownPayPal Phishing Certificates Far More Prevalent Than Previously Thought

in Industry Lowdown