Here’s Why 2017 Will be the Year of the Phish

Phishing attacks will become more prevalent than ever in 2017!

January 28th marks the Chinese New Year. It will be another ‘Year of the Rooster’ per the traditional Chinese lunisolar calendar. Here’s wishing everyone a Happy Chinese New Year!

Respectfully, we at The SSL Store™ have decided to dub 2017 as ‘The Year of the Phish.’

That’s because with all the industry changes that this year has in store, along with the rapid proliferation of free DV SSL, phishing attacks are going to increase exponentially in the coming months.

So let’s talk about phishing—what it is and why it’s about to become a much bigger problem. Then we’ll talk about ways to protect yourself and your business.

What is Phishing?

Vince has discussed phishing in previous blog posts. But if you’re just looking for the abridged version, here’s a quick summary:

As the definition states, phishing is an attempt to obtain sensitive information such as usernames, passwords, and credit card details, often for malicious reasons, by disguising as a trustworthy entity. Many times you see phishing defined in a way that makes it seem like the threat is entirely email-based.

This is inaccurate.

While many phishing attacks do involve the use of email, the practice itself is much more complicated and oftentimes involves the creation of fake websites, fake social accounts and lots of social engineering. Without going too deep into the weeds, social engineering involves creating a believable scenario by which to deceive someone into divulging sensitive or personal information.

So now let’s look at how it all fits together.

How a Phishing Attack Works

As we’ve covered, the whole point of phishing is to trick someone into handing over desirable information – personal info, banking data, login credentials – that can then be used for personal gain.

But, there are two kinds of phishing. There’s the type where a cybercriminal attacks with a specific outcome in mind. This is called spear-phishing and it typically affects larger companies or organizations (though it can still be used against SMBs and private citizens as well). If a group of cybercriminals were to attack a specific company for the purpose of gaining access to its internal network, that would be an example of spear-phishing.

[su_pullquote]”We’ve come a long way since those Nigerian Prince emails.”[/su_pullquote]

Then there’s the type of phishing where cybercriminals are just looking to steal as much information as possible, from as many people as possible. It’s not unlike when you cast a net off a boat while fishing in real life, you’re just looking to pull up whatever the net grabs. There really is no agreed-upon name for this type of phishing, but it’s the variety which is about to see the greatest increase in the next year.

Let’s look at an example of how a well-executed phishing attack might work.

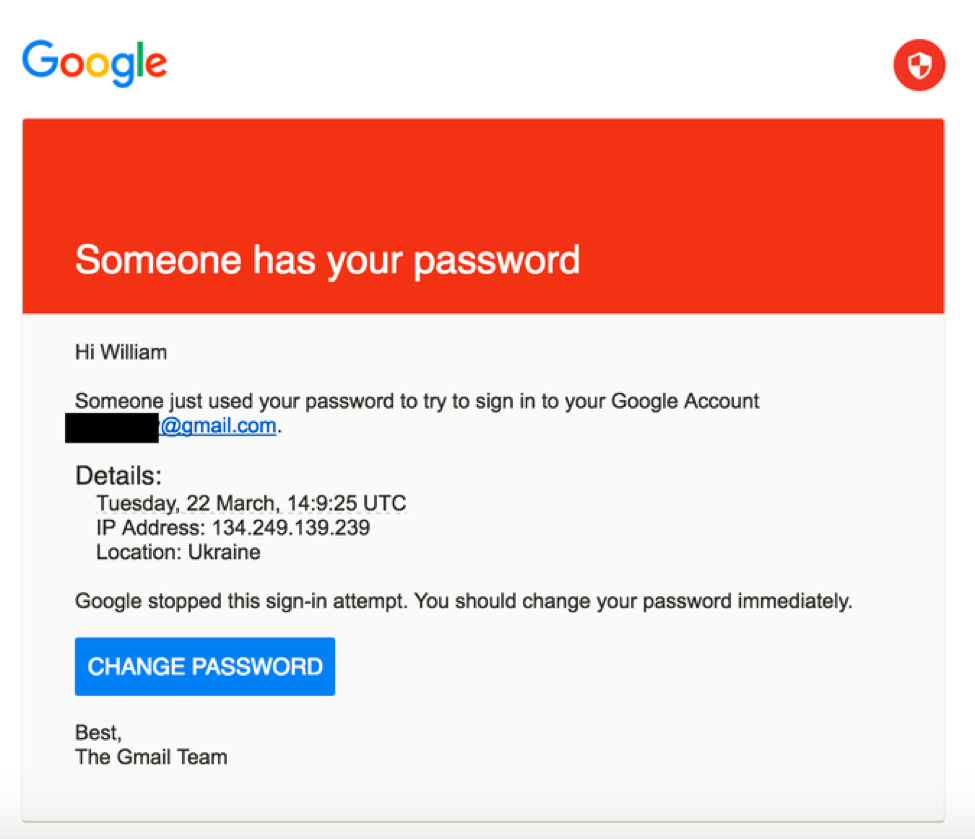

It starts with the cybercriminal contriving a way to contact you that seems believable enough to get you to take the desired action. This is the social engineering element at work and cybercriminals have gotten extremely sophisticated in the ways that they try to trick you. If it’s a spear-phishing attack they could attempt to impersonate your boss or co-worker via email or a messenger service. If the cybercriminals are trying to cast a wider net, they may disguise themselves as an entity, such as a company or organization, that is widely trusted. We’ve come a long way since those Nigerian Prince emails. Nowadays, a phishing email may look more like this:

This is a screenshot of the email that was used to successfully phish John Podesta, the chairman of Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign. It looks authentic. It worked. And keep in mind, the first contact is not limited to emails, it could come in any number of other forms.

Usually, the first contact isn’t what steals the information, though. It can be, but typically it includes a link to a website that is designed to trick you. Once again, cybercriminals have gotten very sophisticated and are capable of creating fake websites that look like carbon copies of the real thing.

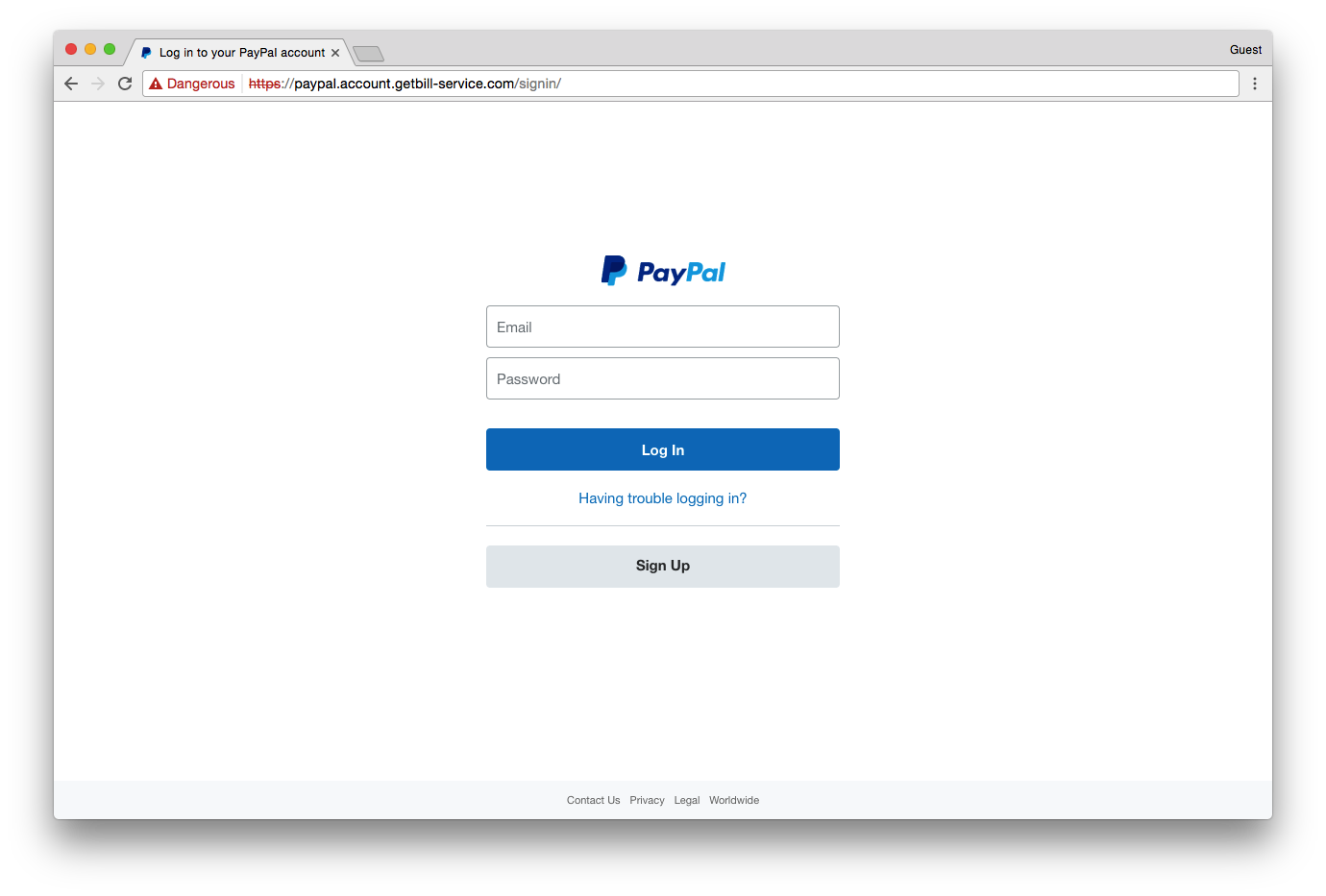

Here’s a real example of a phishing website, in this case, the cybercriminals are attempting to trick you into believing they’re PayPal:

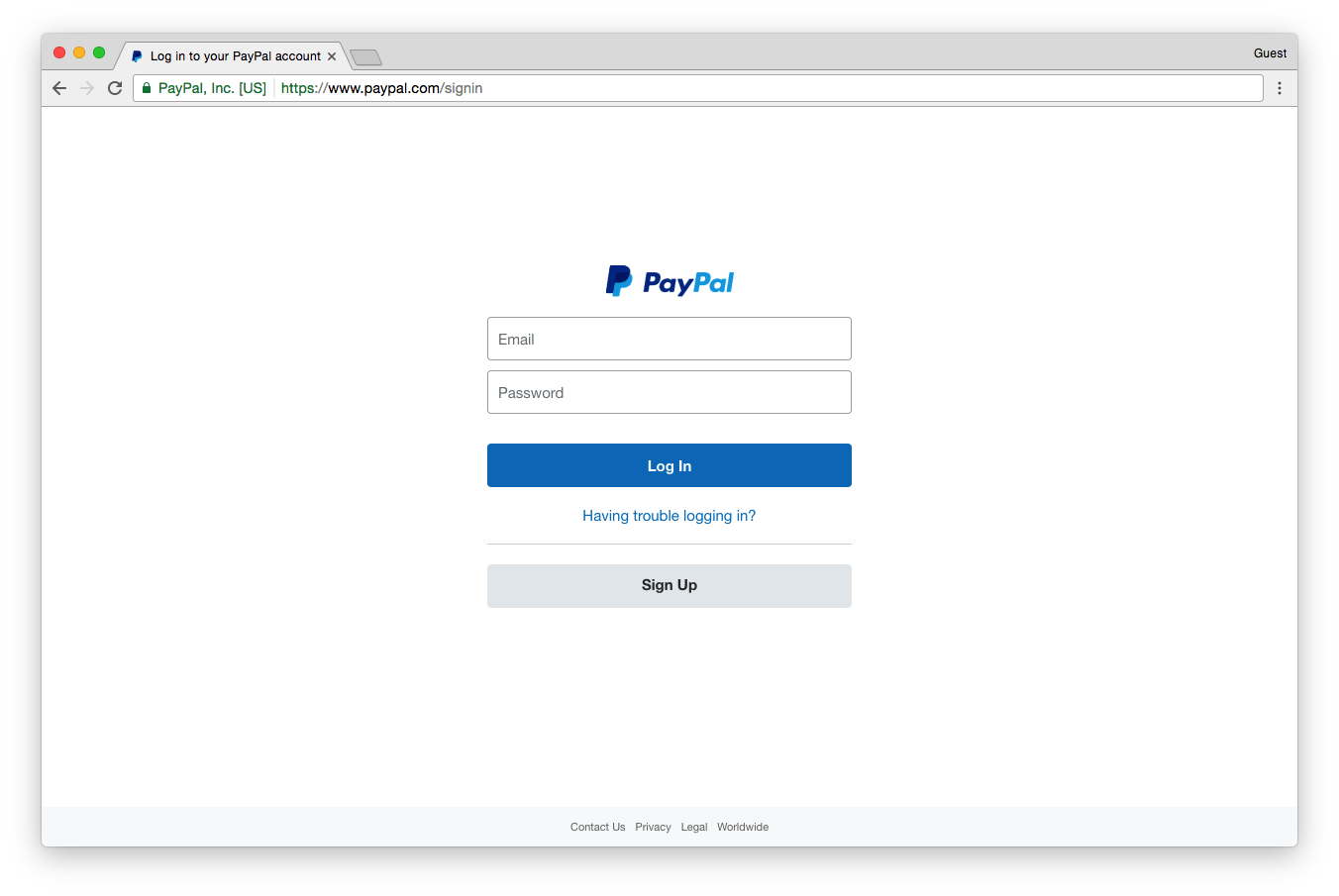

And here’s what the real PayPal login screen looks like:

Could you tell the difference? If you know about Extended Validation SSL and the green address bar, then maybe you could. But that’s assuming that you remember PayPal even has EV SSL in the first place. If you don’t, you’ll notice the fake website does have encryption.

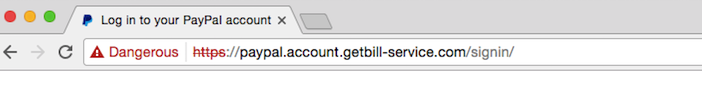

By the point this screenshot was taken, Google had flagged the site as malicious and was issuing an interstitial warning as well as marking the site “Dangerous” in Chrome’s address bar.

But here’s the problem. Google didn’t catch that website right away. That means that for a period of time – in this case a few days – people came to this fake website, saw it was being served over HTTPS and had a green padlock, assumed it was safe and had their information stolen.

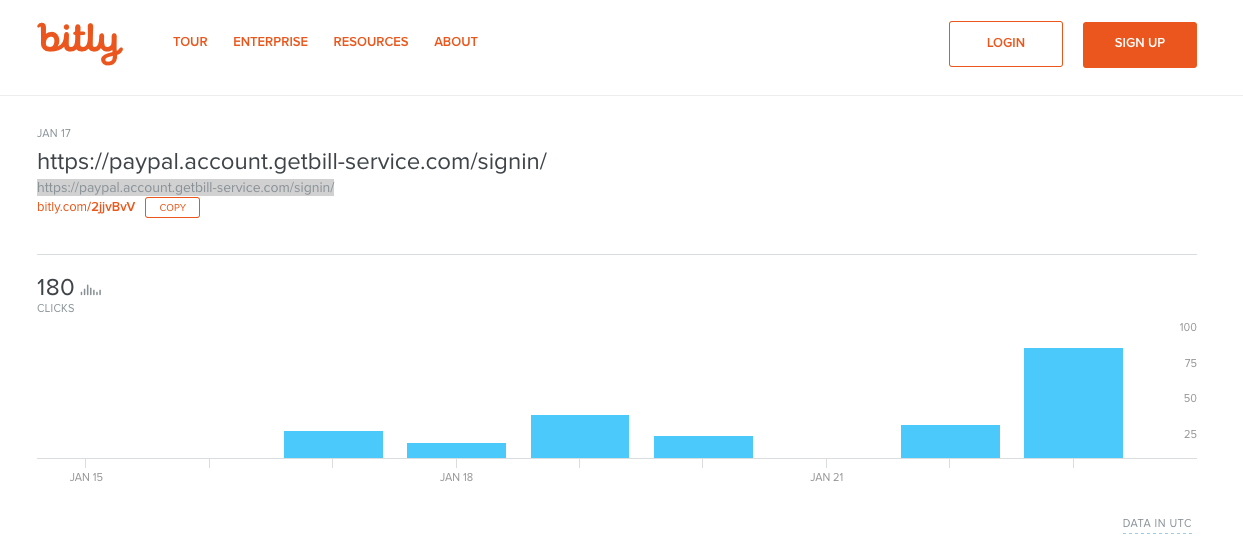

Here’s a breakdown of the traffic that went to this website, courtesy of bit.ly:

When we say that cybercriminals cast a wide net when phishing this way—we mean it. These sites are a dime a dozen (more on that later). It’s now easier than ever to slap a Domain Validated SSL Certificate on them and make them appear safe (we’ll get to that later too). And then, it’s just a matter of how many people they can dupe before Google flags the domain and they have to move on to the next one. This one got at least 180 clicks, and that’s just from one shortened link. There could be dozens of others.

Now let’s look at why phishing attacks are about to increase exponentially.

The Browser Community is Mandating Encryption

This is a good thing, right? Of course! In 2017, the browser community, led by Google and Mozilla, will make a number of moves that all but mandate SSL encryption. Now, Google isn’t going to put a gun to anyone’s head and force them to migrate to HTTPS, but it will penalize websites that don’t encrypt in a severe enough way that it will tip the scales of competitive balance and put them at a severe disadvantage.

Here are some of the ways the browsers are pushing you to encrypt:

- Advanced browser features are exclusive to sites served over HTTPS

- Only encrypted websites can use HTTP/2

- Pages served over HTTPS receive up to a 5% SEO boost

- Emails sent from unencrypted servers will be flagged

- Websites served over unencrypted HTTP will be marked “Not Secure”

It’s that last bullet-point, that unencrypted websites will be marked “Not Secure,” that is going to be the most disruptive. That’s what’s going to more or less force a lot of site-owners to purchase SSL.

As you could probably imagine, having a browser drop “Not Secure” next to your URL in the address bar is hardly the best way for a website to ingratiate itself to its visitors. For any e-commerce website, that kind of negative visual indicator is inevitably going to hurt the bottom line and ultimately the health of the business.

As you could probably imagine, having a browser drop “Not Secure” next to your URL in the address bar is hardly the best way for a website to ingratiate itself to its visitors. For any e-commerce website, that kind of negative visual indicator is inevitably going to hurt the bottom line and ultimately the health of the business.

In this day and age, where people are hyper-aware of online threats and ultra-vigilant about avoiding them, having Google declare your site “Not Secure” is akin to a death sentence.

Here’s what Google’s “Not Secure” indicator looks:

In a few more updates, that indicator will turn red. Mozilla has already announced plans to make similar changes to its security indicators in Firefox, and it’s likely that Apple’s Safari and Microsoft’s Edge browsers will also follow suit.

So here’s the million dollar question: why would this contribute to an increase in phishing?

We’ll get to that in a moment, but first, we need to discuss the other way the browsers’ security indicators are changing.

Sites Served Over HTTPS Will Be Marked “Secure”

On the opposite side of the “Not Secure” indicator, will be the “Secure” label that the browsers will place on sites with encryption. The “Secure” indicator will look like this:

The logic behind this change is debatable because this indicator could actually create a lot of problems. That’s because people tend to associate the word “secure” with safety. And safety is not what the “Secure” indicator is supposed to connote. In the mind of the browser community, it simply indicates that your connection with this site is secure – that it is encrypted and nobody can eavesdrop on it – not that a website is indeed safe.

[su_pullquote align=”right”]”But, what the indicator intends to communicate and how it is perceived differ wildly.”[/su_pullquote]

But, what the indicator intends to communicate and how it is perceived differ wildly. The vast majority of people don’t know to click the security indicator and look at the SSL certificate details, they will simply see the word “Secure” and make the risky assumption that they’re safe. Now, let’s go back to the previous point. More sites than ever will be encrypted, and all of those encrypted sites will be labeled “Secure” by the browsers. This is going to desensitize a lot of people to potential threats.

When every site says either “Secure” or “Not Secure,” many people will function by a simple binary. Sites are either “Secure” and by extension safe, or “Not Secure.” It becomes a quick eye check of the security indicator and then it’s business as usual.

This is dangerous, because it’s now easier than ever to obtain a DV SSL certificate.

Cybercriminals Encrypt Too

Universal encryption is a truly noble initiative, but some of the free SSL services that the initiative has given birth to are creating some unintended outcomes. One of which, is that cybercriminals can now make their phishing websites look even more convincing by adding Domain Validated SSL encryption and turning on the visual indicators that come along with them.

I’m heartened to see a huge increase in adoption of HTTPS by phishermen. pic.twitter.com/DEiAUTDlAA

— Eric Lawrence (@ericlaw) January 23, 2017

Or to put it another way, it’s now easier than ever for cybercriminals to get their malicious websites labeled “Secure.” Then it’s just a matter of how long they can phish before Google catches their site and labels it as malicious. And as we established earlier, that can take days—tricking hundreds of people in the meantime.

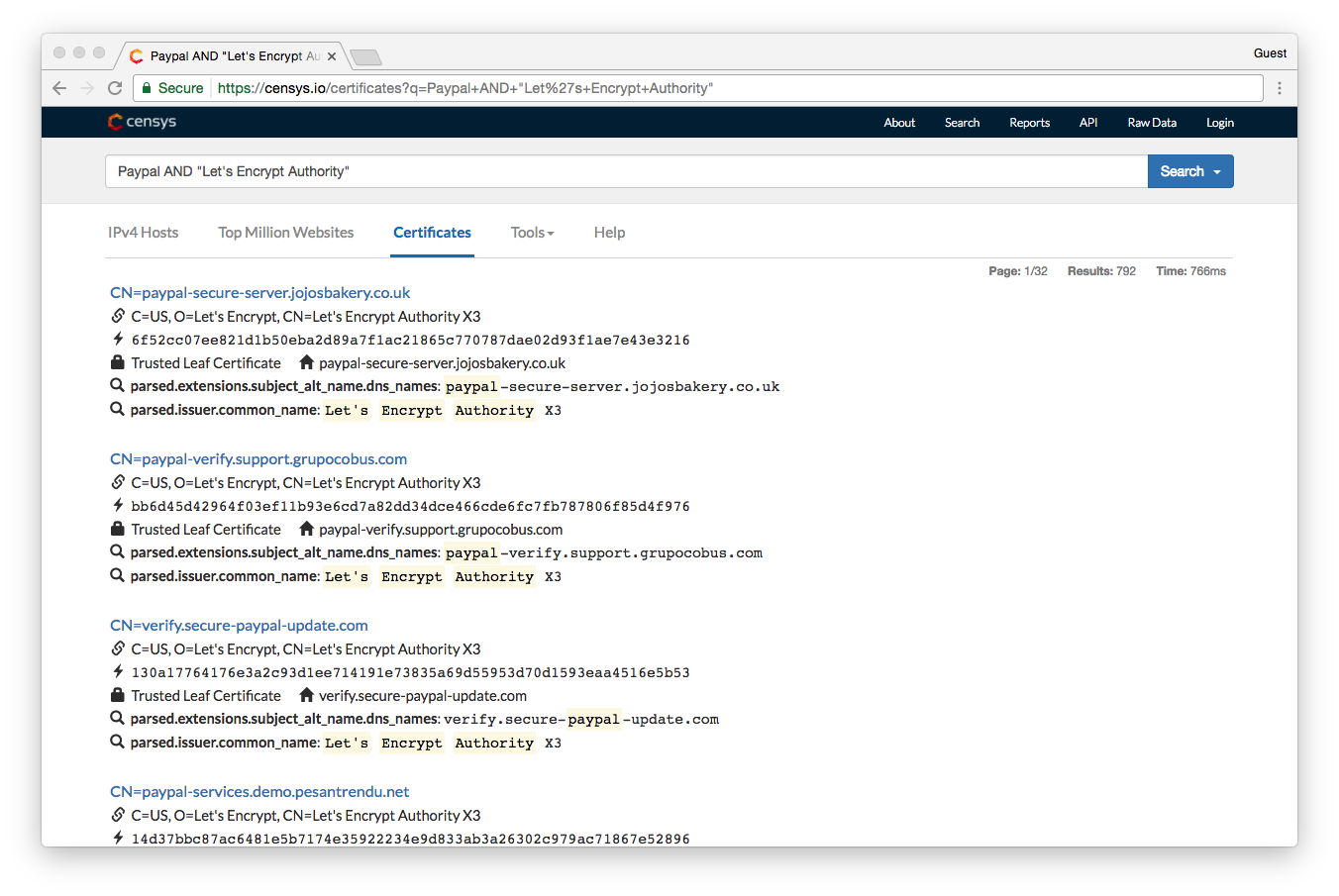

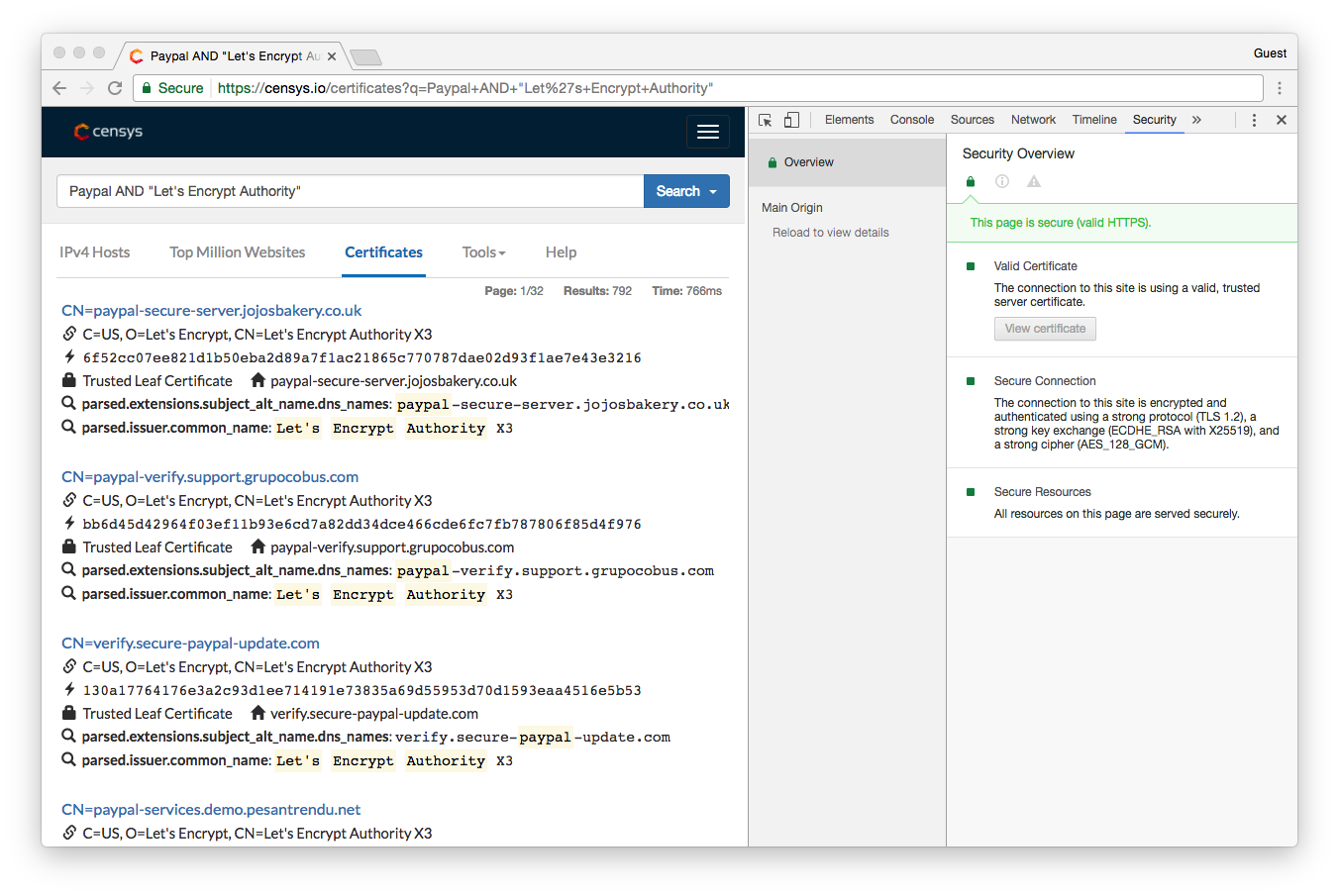

Here’s an example. The CA Let’s Encrypt offers free, DV SSL Certificates. Now, this isn’t meant to pick on Let’s Encrypt, it’s a non-profit organization that relies entirely on donations. Its ability to implement security mechanisms to protect against issuing to negative actors is extremely limited, as such it only checks on the Google blacklist before issuing.

That means any site that isn’t blacklisted by Google can get SSL from Let’s Encrypt.

According to Censys.io, as of January 24, 2017 Let’s Encrypt had issued 792 certificates to websites with the word “PayPal” included in the domain name. A deeper dive into the numbers showed that it was actually closer to 15,000. That’s potentially 15,000 fake PayPal sites that are labeled “Secure” just waiting to phish people until Google finally catches them.

And as you saw earlier, unless you remember that the real PayPal has EV SSL – and the green address bar that comes with it – or you know to click and look at the SSL certificate information, it would be pretty easy to get fooled by any one of those 792 sites.

So Let’s Tie This All Together

So how does this all tie together? It’s a perfect storm, really. The browsers are enacting changes that are aimed at motivating websites – all websites – to get SSL and migrate to HTTPS. Unfortunately, the creation of the “Secure” visual indicator will lull people into a false sense of safety—seeing “Secure” next to the vast majority of websites will create a mindset in many people that as long as they see that green “Secure” indicator, they’re safe.

Couple that with the fact that cybercriminals have easy access to DV SSL, and that their malicious sites will now feature a “Secure” indicator and you have the ideal climate for phishing.

2017 will be the year of the Phish.

So, how do you stay safe and protect yourself?

How to Keep Yourself Safe

As an individual, there are certain steps you can take to protect yourself from phishing. We’ll start with the obvious stuff that you’ve probably heard millions of times. Things like, don’t open email attachments from unknown senders and don’t click on suspicious links. Some cybercriminals are uninspired and happy to stick to the tired old staples—Nigerian princes, lost relatives and frozen bank accounts.

But most cybercriminals have evolved beyond that. As we discussed, they know how to disguise their attempts to make them look like they are from legitimate, trustworthy sources.

That’s why you need to be ever-vigilant—even when everything seems like it checks out OK. Here are three tips that you should always practice to keep you safe from phishing on the internet:

Check the URL

Before you ever click any link, whether it’s from an email or located on a web page, make sure to inspect the URL.

Here’s the URL from the PayPal phishing site we discussed earlier:

In this case, PayPal is a second-level sub-domain. That’s a dead giveaway. The main domain is the name that appears right before the .com. In this case, the actual website you’re at is “getbill-service.com” and not PayPal. We won’t go too in-depth into URL structures, but suffice it to say, if the site you think you’re visiting is not what appears right before the TLD (.com, .org, etc.) then you’re not headed where you think.

Oftentimes cybercriminals will use a link shortening service like bit.ly to hide the actual URL. This is another tip-off. Most legitimate URLs from companies like Google and PayPal are not link-shortened, and if they are it’s done using a custom URL—not bit.ly.

Always inspect the URL before clicking on it. Be sure you know exactly where you’re being sent.

Check the Certificate Details

That “Secure” indicator and the green padlock accompanying it can be clicked. This should be one of the first things you do when you arrive at a page that wants you to login or provide personal information.

[su_pullquote]”Domain Validation SSL provides the same level of encryption security as OV and EV, but you can’t know for sure who is on the other end of the connection.”[/su_pullquote]

In addition to encryption, SSL certificates also offer different levels of authentication. The most basic, DV only requires domain validation – meaning you must only prove you own the domain – before it can be issued. This is the level of validation that cybercriminals exploit because it’s easily obtainable and often free.

The other two levels of authentication, Organization Validation (OV) and Extended Validation (EV), offer what is commonly referred to as Business Authentication. This means that the issuing Certificate Authority actually vetted the business or organization that applied for the certificate and is willing to vouch for their identity.

You can probably see where this is going. Domain Validation SSL provides the same level of encryption security as OV and EV, but you can’t know for sure who is on the other end of the connection. If you see that a website has DV SSL, be extremely cautious. You can’t be sure who you’re sending your information to.

On the other hand, OV and EV SSL Certificates will display verified business details about the company that runs the site. You can’t fake this. If you see verified business details, you know who you’re dealing with.

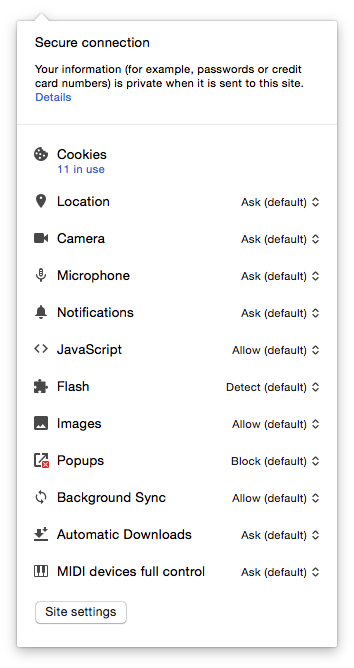

To check certificate details, click the “Secure” indicator, that will bring up this screen:

Click on the word “Details” to open up “Security Overview.”

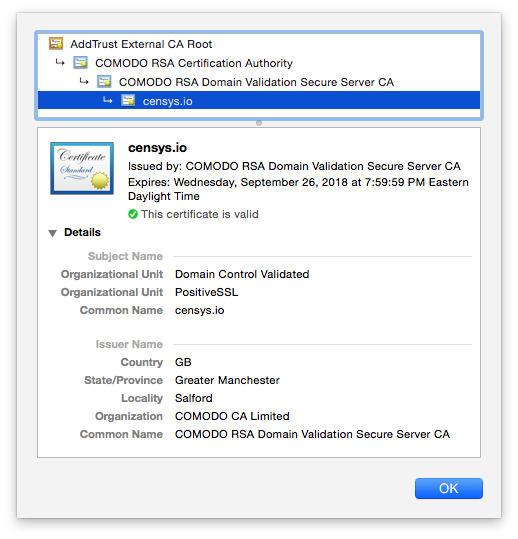

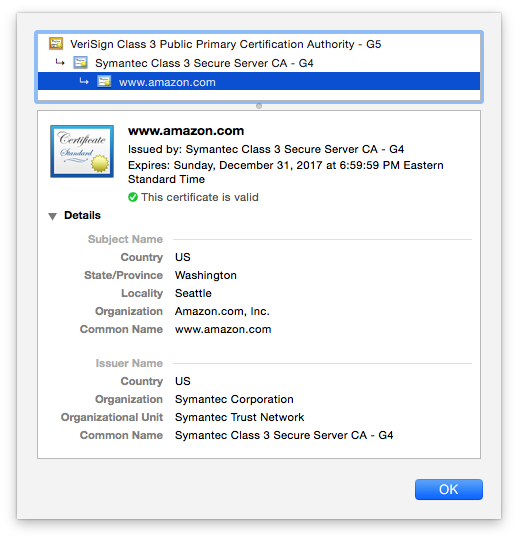

Click on “View Certificate” to open the certificate details.

Above is an example of a Domain Validated certificate. Notice how it doesn’t give you any information about who owns the site? It just says the name of the site itself. Who knows who is running it. Below is an example of an Organization Validated certificate, notice the legal name of the organization is displayed? Now there’s no doubt who owns this site.

As for EV SSL…

Check for the Green Address Bar

The most unmistakable way to show a site is the legitimate article is with the green address bar that accompanies EV SSL. Granted, the address bar is no longer green like it used to be—now it just displays the organization’s name and country of origin in green font next to the URL. But still, this visual indicator is unmistakable and un-fakeable.

If you see a green address bar, you don’t even need to check the certificate details because you already have verification that the site is legitimate.

[su_pullquote align=”right”]”The best way to avoid being phished is just to pay attention. Be vigilant.”[/su_pullquote]

EV SSL can be cost-prohibitive for a lot of smaller businesses or organizations, but most major companies and corporations do invest in Extended Validation. So, if possible, try to keep a running tally in your head of which sites have EV. As you saw in our PayPal example from earlier, that could be the difference between getting phished and knowing when a site is fake.

The best way to avoid being phished is just to pay attention. Be vigilant. Take a moment to click around and check where your links are taking you and who is on the other end of your encrypted connections.

Moving forward in 2017, all connections may now be encrypted, but you know better than to think that means you’re safer. Nowadays, it’s all about knowing who exactly you’re connected with.

How to Protect Your Business

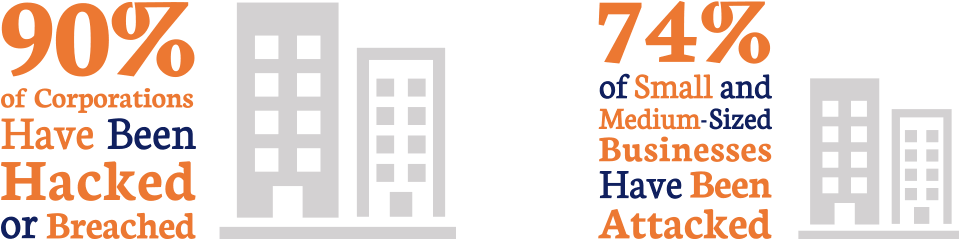

You may not think your company or organization would be at risk of a phishing attack. You would be wrong.

Now think about this, according to the Nation Cyber Security Alliance, 60% of the small businesses that get hit by a cyber attack go under within six months of the incident. Getting phished does major harm to your reputation and costs you money.

[su_pullquote]”Frankly, DV SSL might even be putting your customers at risk [of being phished].”[/su_pullquote]

As you can probably surmise, the best way to avoid this issue entirely is to invest in SSL that also provides business authentication. OV SSL is the more affordable route, but going with OV may also require you to educate your customers about SSL indicators and how to make sure they’re at the right website. Extended Validation SSL is frankly the best option, as it provides an instantly recognizable visual indicator that offers immediate assurance to anyone who visits your site. As we discussed though, EV can be cost prohibitive.

Just stay away from Domain Validation SSL. In 2017, with the current environment, any websites that deal in personal information or financial data need more authentication than DV can possibly offer. Frankly, DV SSL might even be putting your customers at risk.

2017: The Year of the Phish

And there you have it, that’s why 2017 will be the Year of the Phish. In a constantly evolving game of cat and mouse between cybercriminals designing fake, phishing websites and the browsers tasked with catching and blacklisting them—the advantage has shifted towards the cybercriminals in 2017.

New security indicators, the proliferation of HTTPS and the ease with which cybercriminals can get SSL and disguise their sites as “secure” have created the perfect climate for phishing.

So stay vigilant—don’t get duped in 2017.

![A Look at 30 Key Cyber Crime Statistics [2023 Data Update]](https://www.thesslstore.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/cyber-crime-statistics-feature2-75x94.jpg)

5 Ways to Determine if a Website is Fake, Fraudulent, or a Scam – 2018

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityHow to Fix ‘ERR_SSL_PROTOCOL_ERROR’ on Google Chrome

in Everything EncryptionRe-Hashed: How to Fix SSL Connection Errors on Android Phones

in Everything EncryptionCloud Security: 5 Serious Emerging Cloud Computing Threats to Avoid

in ssl certificatesThis is what happens when your SSL certificate expires

in Everything EncryptionRe-Hashed: Troubleshoot Firefox’s “Performing TLS Handshake” Message

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityReport it Right: AMCA got hacked – Not Quest and LabCorp

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityRe-Hashed: How to clear HSTS settings in Chrome and Firefox

in Everything EncryptionRe-Hashed: The Difference Between SHA-1, SHA-2 and SHA-256 Hash Algorithms

in Everything EncryptionThe Difference Between Root Certificates and Intermediate Certificates

in Everything EncryptionThe difference between Encryption, Hashing and Salting

in Everything EncryptionRe-Hashed: How To Disable Firefox Insecure Password Warnings

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityCipher Suites: Ciphers, Algorithms and Negotiating Security Settings

in Everything EncryptionThe Ultimate Hacker Movies List for December 2020

in Hashing Out Cyber Security Monthly DigestAnatomy of a Scam: Work from home for Amazon

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityThe Top 9 Cyber Security Threats That Will Ruin Your Day

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityHow strong is 256-bit Encryption?

in Everything EncryptionRe-Hashed: How to Trust Manually Installed Root Certificates in iOS 10.3

in Everything EncryptionHow to View SSL Certificate Details in Chrome 56

in Industry LowdownPayPal Phishing Certificates Far More Prevalent Than Previously Thought

in Industry Lowdown