The Ultimate Guide to 13 U.S. Data Privacy Laws (And What They Mean to Your Business)

It seems like every time you turn around, new U.S. data privacy laws are popping up. The United States is an expansive country made up of 50 individual governing states, many of which are taking different approaches to protecting data privacy. We’ll explore the list of U.S. data privacy laws by state.

There are dozens of data security and encryption laws that have popped up globally over the past couple of decades. The same can be said regarding data privacy laws in the U.S. However, not all of them passed muster and continued on to be signed in their state or country. With the increasing expectation of data privacy amongst consumers, it makes sense that we’d see an influx in these laws in the U.S.

That’s why this article will focus on the 13 data privacy laws in the U.S. that have been signed, and how they can (or will) impact your organization’s data security systems and processes.

If you’re planning to read this article the whole way through, great! Just be sure to grab yourself a cup of coffee — you’re going to be here a while. Otherwise, if you don’t want to slog through all states’ laws, select your state of interest in the Table of Contents list below.

Let’s hash it out.

Table of Contents for U.S. Data Privacy Laws (Listed By State)

- It seems like every time you turn around, new U.S. data privacy laws are popping up. The United States is an expansive country made up of 50 individual governing states, many of which are taking different approaches to protecting data privacy. We’ll explore the list of U.S. data privacy laws by state.

- Why We Have State Laws Instead of a Federal (U.S.) Data Privacy Law

- A Breakdown of the 13 U.S. Data Privacy Laws (By State)

- 1. California — California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA)

- 2. Colorado Privacy Act (CPA)

- 3. Connecticut — Act Concerning Personal Data Privacy and Online Monitoring (CTDPA)

- 4. Delaware Personal Data Privacy Act (DPDPA)

- 5. Florida Digital Bill of Rights (FDBR)

- 6. Indiana Consumer Data Protection Act (ICDPA)

- 7. Iowa Consumer Data Protection Act (IDPA)

- 8. Montana Consumer Data Privacy Act (MCDPA)

- 9. Oregon Consumer Data Privacy Act (OCDPA)

- 10. Tennessee Information Protection Act (TIPA)

- 11. Texas Data Privacy and Security Act (TDSPA)

- 12. Utah Consumer Privacy Act (UCPA)

- 13. Virginia Consumer Data Privacy Act (CDPA)

Why We Have State Laws Instead of a Federal (U.S.) Data Privacy Law

“Everybody wants a federal privacy law,” said Debra J Farber, a Privacy Tech Advisor and Strategist during a podcast interview with privacy evangelist Robert Bateman. “This is why we can’t have nice things. It’s because no one could agree what goes in that law. And the things that we can’t agree on don’t have anything to do with privacy itself.”

Frankly, she’s right. There are many politicians from every state who want to have their say and stick their hands in the pot. (Ah, bureaucracy.) With that many egos and individual agendas, there’s no way to have a consensus about what should or shouldn’t be included in a federal law.

So, for now, we’ll focus on what individual states are doing with regard to laws that have been signed into law as of the writing of this article (January 2024).

A Breakdown of the 13 U.S. Data Privacy Laws (By State)

For those of you who bothered skimming ahead and counting the listed pieces of legislation in the article, you might argue that there are 15 laws listed instead of 13. Our response? We’re saying 13 because 2 of the pieces of legislation that we’ll cover either amend or add to the CCPA specifically, so we’re not giving them separate numbers in the overall list count.

Anyhow, there’s way too much information to dive in-depth into each of these laws. So, we’ll try to just hit the highlights and identify the things you want (and need to know):

- What each law is,

- What it does (in terms of consumer rights),

- Who it applies to, and

- How it impacts (or will impact) your business once in effect.

Generally speaking, the majority of these laws cover many of the same things:

- Requiring businesses to respond to authenticated consumer requests to exercise their rights under the law. Emphasis on authenticated requests. Many of the laws don’t specify how the consumer is to be authenticated; rather, they just say that they must be authenticated by “reasonable means.”

- Ensure that covered consumers or residents have the right to access, correct, delete, and opt out of sharing and/or selling their personal data for certain uses.

- Require covered organizations to provide privacy notices on their websites that inform consumers or state residents about how they can exercise their rights under the respective law.

- Have specific requirements relating to the sharing and processing of de-identified data or pseudonymous data. (In many cases, however, this data is excluded from consumer data requests.)

- Require organizations to implement physical, technical and administrative security protections, controls and practices to secure data. Although many laws don’t explicitly mention encryption (e.g., SSL/TLS encryption) as a security measure, it’s certainly something that would fall under the umbrella of “reasonable security.” Of course, if you’re using digital certificates to protect data in transit, then you’ll need to also ensure that you’re adhering to certificate management best practices.

- Prohibit the use of this data for discriminatory practices (charging different prices, denying goods or services, etc.)

- Protect the personal data of children and teenagers (although the ages often range from 13 to 16, depending on the specific law).

- Require businesses to establish appeal processes and, in some cases, establish “universal mechanisms” for opt-out requests.

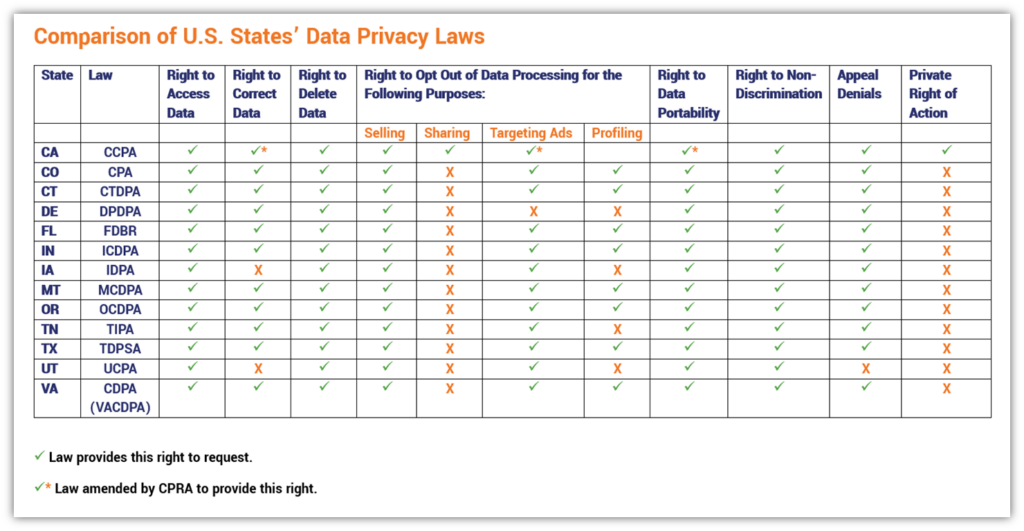

Here’s a quick overview of the different laws and the rights they provide:

One of the interesting differences between many of the laws is how they define or categorize “persona” and “sensitive” data. For example, while most laws include “sexual orientation” or “sex life” as covered categories of sensitive data, some states (i.e., Delaware and Oregon) specifically mention nonbinary and transgender statuses in their definitions.

Of course, there are also plenty of particulars each law includes in its requirements — and we can’t cover all of them in this article. But we will briefly cover the key points of each law individually in the content below. To keep things easy, we’ve organized the laws by state (and alphabetically for states that have more than one law we’ve covered).

1. California — California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA)

What It Is

The California Consumer Privacy Act (Assembly Bill No. 375 [AB-375]) was enacted in 2018 and served as the first-of-its-kind legislation in the United States. Loosely based on the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), it serves to protect California consumers by supporting their rights regarding the processing, use, storage, and deletion of their personal data.

While CCPA served as a starting point, many states have since shifted to data privacy and security laws modeled after Virginia’s state law.

What It Does

The CCPA outlines several crucial rights of consumers (or their authorized representatives):

- Right to know what personal or biometric information a business collected about them in the previous 12 months (and how that information is collected, shared, or sold),

- Right to opt out of having their information collected and/or sold,

- Right to delete data (with some exceptions), and

- Right to not be discriminated against or penalized for exercising their rights to delete or opt out of data collection, storage, or usage under the CCPA.

Of course, this law doesn’t only apply to data collected over the internet or via other electronic means; it also applies to all types of consumer data that businesses collect, regardless of how it’s collected.

Who the Law Applies To

Does the law apply to you? It depends. If you’re an organization that meets one or more of the following thresholds, then yes:

- Achieves $25+ million in annual gross revenues.

- Buys, receives, sells, or shares the personal info of 50,000+ consumers, households, or devices annually.

- Gets 50% of its annual revenues from the sales of consumers’ personal data.

How It Affects Your Business

Now that we know what the law does and who it applies to, let’s bring it all home to see what this means from a business’s perspective. In a nutshell, you’re expected to:

- Clearly disclose to California consumers what personal information is being collected, used, and stored (upon request);

- Provide a means for affected consumers to opt out with a “Do Not Sell My Personal Information” page on your site;

- Face non-compliance penalties or payments for damages caused by CCPA disclosure violations (intentional or otherwise);

- Disclose information to a consumer within 45 days of receiving a verifiable request (although not more than twice in a 12-month period).

A couple of years after the CCPA was released, another piece of legislation was published that amended certain components of the law. That’s what we’re going to discuss next.

California Privacy Rights Act of 2020 (CPRA)

What It Is

Before we go any further, let’s quickly clarify one important point: although it’s commonly referred to as such, CPRA is not a new law. Rather, it’s strictly an amendment of the first law (CCPA), and as such, is often referred to as “CCPA, as amended.” It also sets the groundwork for establishing the California Privacy Protection Agency (CPPA) in 2020.

Ugh. CCPA, CPPA, and CPRA. Gee, that’s not confusing at all…

Now that we have all of that out of the way, let’s continue with exploring this amendment.

What It Does

CPRA, which kicked into effect on January 1, 2023 (with a few provisions that kicked in on July 1, 2023), serves to amend the language of the 2018 CCPA and updates the state’s civil code. In a nutshell, it was passed as part of Proposition 24, and gives consumers additional rights on top of those provided by CCPA:

- Correct inaccurate personal information, and

- Limit the use and disclosure of their sensitive information.

Does this mean that the CCPA requirements are no longer valid now that CPRA has kicked into effect? Not quite. While CPRA’s amendments are now in effect, the non-amended CCPA requirements are also still in effect.

Who the Law Applies To

As a business or organization that collects, uses, or stores the personal information of California consumers, this means you must abide by the rules of the CCPA, including the amendments specified in CPRA, if you meet at least one of the following criteria:

- Your organization has $25+ million in annual gross revenues in the preceding calendar year;

- You buy, sell, or share the personal information of “100,000 or more consumers or households” (which doubles the CCPA’s 50,000-consumer requirement and removes the “devices” from that part of the language); and/or

- Your organization derives at least 50% of its annual revenues from selling or sharing consumers’ personal information.

While this applies to many businesses, including data brokers, there are exemptions for certain businesses as stipulated under the state’s Civil Code section 1798.99.80.

How It Affects Your Business

So, what does all of this mean for you? Businesses that control the collection of personal data shall “at or before the point of collection,” inform consumers about the following:

- What categories of information have been collected during the “applicable period of time” (no longer specifying 12 months),

- Why the data is being collected,

- Whether the information will be shared or sold, and

- How long the business will retain the personal info.

For consumers who submit CPRA requests, businesses must provide, update, or delete the consumer’s personal information within 45 days of receiving a verifiable request. If an extension is needed, the business must provide adequate notice to the customer within the first 45-day period.

The DELETE Act of 2023

What It Is

Senate Bill 362 “Data Broker Registration: Accessible Deletion Mechanism,” more commonly known as the Delete Act, is another piece of legislation that builds upon the CCPA. More specifically, it aims to streamline the process consumers must go through to exercise their CCPA rights. The goal is to establish a one-stop place where California residents can go to delete their personal data held by businesses quickly and easily.

Senate Bill (S.B. 362) was signed into law on Oct. 10, 2023. The CPPA’s deletion mechanism must be created by Jan. 1, 2026, and will involve a series of phased rollouts that span out to 2028.

What It Does

It shifts many of the responsibilities regarding the CCPA, CPRA, and data broker-related provisions to the California Privacy Protection Agency (CPPA). It also calls for the creation of an “accessible deletion mechanism” that enables California consumers to request all data brokers’ (and their associated service providers or contractors) delete their data “through a single verifiable consumer request.”

Basically, starting Jan. 1, 2026, the CPPA must have an established place for consumers to go (e.g., a single webpage) to submit a single request to have their information deleted.

Who the Law Applies To

Data brokers, which are defined as “a business that knowingly collects and sells to third parties the personal information of a consumer with whom the business does not have a direct relationship.” All applicable data brokers must register through the California Privacy Protection Agency by no later than Jan. 31 following the year in which a business first meets the “data broker” definition.

How It Affects Your Business

If you’re a data broker, then here are some of the ways that the bill will impact you starting on the following dates:

- Jan. 31: Organizations that meet the definition of a data broker, on or before this date each year, must register with the CPPA and pay any registration fees. If you fail to register, you’ll face administrative fines and will face administrative actions. There are additional reporting requirements that must be met before July 1 following each year your organization meets the definition of a data broker.

- Starting Aug. 1, 2026: Every 45 days, you’ll have to access the mechanism and process the deletions (with exceptions). The bill stipulates that the CPPA can charge a fee to access the mechanism.

- Jan. 1, 2028: Starting on this date and every three years after, you’ll undergo a third-party audit to verify your compliance and will be required to submit a report of said audit to the CPPA (upon written request).

Data brokers who fail to meet the registration requirements will be fined at least $200 daily to cover any administrative and investigative expenses that will be incurred by the CPPA relating to the violation. A $200 fine also applies (deletion per request) for data brokers who fail to delete data as requested.

2. Colorado Privacy Act (CPA)

What It Is

The Colorado Privacy Act (CPA), which was signed on July 7, 2021 as Senate Bill 21-190 (SB 21-190), took effect on July 1, 2023. According to the legislative text, the law aims to make Colorado “among the states that empower consumers to protect their privacy and require companies to be responsible custodians of data as they continue to innovate[.]”

The CPA offers protection to Colorado consumers in non-professional contexts, meaning in their individual or household lives. (It doesn’t offer the same protections for Colorado residents in their employment-related contexts.)

What It Does

The Colorado CPA enables consumers to have greater control of the data that data controllers can collect, use, sell, and share. For example, it protects the following rights:

- Know what personal information is being collected about them.

- Access to the data in an easy-to-access format.

- Make corrections to or delete any of the individuals’ personal data.

- Opt out of the collection, use, and sale of data collected for “targeted advertising and certain types of profiling.”

But what exactly is considered “personal data” in this situation? It depends on the context. Generally speaking, any sensitive data linked (or reasonably linked) to a consumer that isn’t de-identified, publicly available (i.e., government-provided information or information shared publicly by consumers), or collected via employment or business-to-business interactions.

Who the Law Applies To

The law applies to organizations, including non-profits, that conduct business in CO and meet one or both of the following:

- Control or process the personal data of 100,000 Colorado residents each calendar year, or

- Generates revenue or receives discounted services as the result of processing or selling 25,000 Colorado residents’ personal data.

It also applies to the vendors, contractors, or service providers who handle the sensitive consumer data provided by these organizations. However, there are exceptions for some depending on their compliance requirements (see §6-1-1304 of the CPA) for additional info.

How It Affects Your Business

There are many ways this law affects you if you’re doing any business involving Colorado residents because it’s focused on transparency and informed consent. As such, you must:

- Be open about what you’re collecting and using the data for and respond to residents’ requests for information.

- Get affirmative consent from users in multiple circumstances and use the data for your specified purpose(s) only.

- Clearly define your role as a data collector or processor. If your organization qualifies as both, then it’ll fall under the controller categorization by default.

- Carry out data protection assessments prior to selling or processing personal or sensitive data.

- Secure the data using “reasonable security practices.”

3. Connecticut — Act Concerning Personal Data Privacy and Online Monitoring (CTDPA)

What It Is

Connecticut’s Act Concerning Personal Data Privacy and Online Monitoring (CTDPA) — This law, Senate Bill No. 6, was signed by Governor Ned Lamont on May 10, 2022, and took effect July 1, 2023. Called the Public Act 22-15, this law offers a “comprehensive series of protections for consumers that provide them with greater ability to safeguard their personal data that is collected when they interact with companies online.”

What It Does

In a nutshell, the CTDPA outlines several crucial rights of Connecticut residents, including the rights to request the following with regard to the sale, processing, and/or usage of their personal data for targeted marketing:

- Access (in a usable format)

- Correct

- Delete

- Opt out

Who the Law Does Applies To

The law applies to businesses that control or process the personal data of

- 100,000+ consumers (except for data collected for completing payment transactions), or

- 25,000+ consumers and also receive 25%+ gross revenue from the sale of that personal data.

Another group of organizations that are categorized as covered businesses are service providers that maintain or provide services involving the use of protected personal data.

Organizations that don’t necessarily fall under the purview of this law include governments, nonprofits financial institutions, and healthcare entities (among others). There are plenty of exceptions to read about based on compliance reasons and other considerations.

How It Affects Your Business

The new law outlines the requirements that covered entities must abide by regarding the collecting, managing, processing, storing, and deleting of Connecticut residents’ personal data. For example:

- Limit the amount of data to what’s “adequate, relevant and reasonably necessary” for your intended disclosed purpose.

- Respond to verified CTDPA requests “without undue delay” as long as it’s within 45 days after the request was received. (You can request an extension, though, in some cases.)

- Implement and maintain technical and physical security measures that protect CT residents’ private data and access to it.

There are set requirements for controllers and processors alike. A contract is called for to govern how a processor handles the data on behalf of the controller. The controller must specify the instructions and guidance, and object to anything questionable.

If you violate the CTDPA, you also may face civil penalties (up to $5,000 per violation) and have to pay potential injunctive relief or reparations.

4. Delaware Personal Data Privacy Act (DPDPA)

What It Is

Delaware Personal Data Privacy Act (DPDPA) — The bill, known otherwise as Delaware House Bill 154 (H.B. 154), was signed by Gov. John Carney on Sept. 11, 2023 and will kick into effect on Jan. 1, 2025.

Like several other states’ data privacy laws, the DPDPA protects data for household and personal purposes — meaning those not collected and processed for employment- and commercial-related use cases. It also doesn’t allow affected Delaware residents any private rights to action, meaning they don’t have the right to sue organizations that violate their rights under this law.

What It Does

The DPDPA outlines several crucial rights of consumers regarding the collection and processing of their personal data in non-employment-related contexts (except for data that would reveal a controller’s trade secrets). For example, consumers can:

- Verify and access any personal data that a controller possesses and processes.

- Obtain an easily accessible copy of the personal data a controller has.

- Obtain a “list of the categories of third parties” that the controller has disclosed data to.

- Correct any inaccurate information that may exist within the resident’s personal data.

- Request a controller delete their personal data outright.

- Opt out of having their data processed for profiling and targeted advertising.

Who the Law Applies To

The law applies to individuals and organizations that targeted Delaware residents the previous year and meet one or both of the following criteria:

- Conducts business that controls or processes the data of at least 35,000 Delaware consumers, OR

- Conducts business that controls or processes the data of at least 10,000 consumers and also derives 20%+ of its gross revenue from its sales.

Of course, there are some exceptions in terms of businesses that the law doesn’t apply to (regulatory and state administrative bodies, financial institutions, national securities associations, etc.). However, the rules (surprisingly) don’t apply in the case of higher education institutions and most (though not all) non-profits. Be sure to read the law’s text for additional information.

How It Affects Your Business

Much like the CCPA, organizations categorized as controllers and processors each have lists of requirements to abide by. For example, controllers can’t discriminate against residents who exercise their data privacy rights by offering different prices, different quality of goods or services, etc. They’re also required to provide consumers with a way to revoke their consent and submit opt-out requests, if they so choose.

Of course, if you work for the Delaware Department of Justice, you’ll need to begin public education and outreach at least six months prior to the law’s July 1, 2024 effective date. (That deadline is right around the corner, so you better get started now!)

5. Florida Digital Bill of Rights (FDBR)

What It Is

Florida Digital Bill of Rights (FDBR) — The state’s digital rights bill (Senate Bill 262 [S.B. 262]) was signed into law by Governor Ron DeSantis on June 6, 2023 and is set to take effect starting July 1, 2024. This one, in particular, hits close to home for us here at The SSL Store, since we’re based in St. Petersburg, Florida (i.e., about 1.5 hours west of Orlando).

This law largely targets “Big Tech” companies rather than midsize businesses, meaning that it applies to significantly fewer businesses than other states’ data privacy laws. (We’ll explain that more in a bit.)

What It Does

The FDBR outlines several rights of state consumers:

- Gives them greater access to and control of their personal data (to access it, delete it, etc.), which includes biometric and geolocation data.

- Prohibits the use of covered personal data for discriminatory practices that can affect a consumer’s ability to buy a home, get a job, or obtain health insurance.

- Enables consumers to opt out of having their data sold or processed for profiling and targeted advertising.

One of the most interesting components of this bill is that it aims to inform state consumers about how search engines (e.g., Google) manipulate search results to prioritize or deprioritize results based on “political partisanship or political ideology” or monetary considerations. As part of the new law, any applicable controllers operating a search engine also must clearly describe what parameters are considered in determining search engine rankings.

Want to opt out of your voice (via voice recognition), biometric data, or location being collected? You can do that under the law with just a few notable exceptions.

However, something the law doesn’t do is establish a private cause of action (meaning that consumers can’t enforce their rights or seek punitive damages or other remedies under the law).

Who the Law Applies To

Truthfully, this law is blatantly targeting the “Big Tech” companies. Why do we say that? The law applies to for-profit organizations that conduct business within Florida, collect and determine the purpose of processing consumers’ personal data, and make $1+ billion in global gross revenues each year, in addition to meeting one or more of the following:

- Gets at least 50 percent of its global gross annual revenues from online ads (including targeted advertising),

- Includes a cloud-based consumer smart speak and voice command component that uses “hands free verbal activation), excluding those associated with motor vehicles, OR

- Operates an app store (or another type of digital distribution platform) containing 250,000+ unique software apps users can install.

Yeah… As you can see, with these stipulations, small and mid-size businesses don’t meet such criteria.

How It Affects Your Business

Unless you work for one of those mega tech firms (i.e., the “Googles” of the world), it really doesn’t impact your business.

However, if you are one of those big tech companies, then you should know the following:

- Violations may result in civil penalties of up to $50,000 per violation. However, these fines may be tripled in certain instances:

- Processing of known children’s personal data.

- Failing to correct or delete a consumer’s data.

- Selling consumer data after a consumer has opted out.

The law also sets additional requirements and limitations, which include:

- Getting consent before processing data.

- Limiting what personal data you can collect to what’s reasonably necessary and relevant in its purpose.

- Providing “reasonable administrative, technical, and physical data security practices” to protect the covered personal data.

6. Indiana Consumer Data Protection Act (ICDPA)

What It Is

Senate Bill 5, also known as the Indiana Consumer Data Protection Act (ICDPA), was signed into law by Gov. Eric Holcomb on May 1, 2023. It’s legislation that aims to give control of personal data back to Indiana state residents by attesting to their rights and also outlining the responsibilities of controllers and processors that handle consumer data.

The new law is set to take effect on Jan. 1, 2026. (Yeah, we know, that’s a lengthy rollout period — it’s actually the furthest out on the calendar when compared to other states’ similar laws that we’ve covered in this article.)

What It Does

The ICDPA outlines several crucial rights of consumers as well as exemptions to what personal data can (or can’t) be collected, processed, stored, or deleted. In Indiana, this views state residents from a strictly personal/household perspective; the law doesn’t apply to personal data used in employment or commercial contexts.

Much like other data privacy laws in the U.S., the ICDPA also enables consumers to do the following:

- Confirm what data, if any, a controller is processing and have access to it.

- Receive a copy (or representational summary) of the data.

- Correct any inaccurate information within those records.

- Delete personal data they don’t want the controller to have or process (with some exceptions).

- Opt out from having their data sold or processed for targeted advertising or profiling.

However, unlike several other U.S. data privacy laws, there is no private right of action for Indiana residents.

Who the Law Applies To

The law applies to anyone who conducts business in Indiana or produces products or services targeting state residents who meets the following requirements:

- Processes or controls 100,000+ Indiana residents’ personal data, or

- Processes or controls the personal data of 25,000+ Indiana residents whose revenues (at least 50%) are derived from sales of that data.

As with many of the other passed data protection laws, the ICDPA also notes many categories of organizations that are exempt from this rule. Most notably, state authorities, public utilities, healthcare organizations, etc.

How It Affects Your Business

If you’re collecting and/or processing data for the purposes of employment (i.e., checking to see if someone has anything questionable in their background), then this law doesn’t necessarily apply to you.

Indiana is one of the states requiring controllers and processors to agree on how consumer data gets processed and outlines the rights and responsibilities of each party. They literally have to have a contractual agreement that spells it out.

As a data controller, you must respond to a consumer’s authenticated request “without undue delay” and no later than 45 days after receiving their request (although they can be granted up to a 45-day extension so long as they inform the consumer).

The law affords businesses a 30-day cure period for alleged violations. However, violations that go unaddressed beyond that period may result in injunctions and civil penalties costing upwards of $7,500 per violation, as well as investigative and legal-related costs.

7. Iowa Consumer Data Protection Act (IDPA)

What It Is

Iowa Consumer Data Protection Act (called either the ICDPA or IDPA, depending on the source) aims to outline the rights of Iowa residents and the responsibilities of businesses that control or process their data. The bill was signed into law by Gov. Kim Reynolds on March 28, 2023 and is set to go into effect Jan. 1, 2025.

What It Does

Much like the Montana Consumer Data Privacy Act we’ll cover next, the Iowa data privacy law outlines the types of personal data that are protected, including “precise geolocation data,” which identifies a person’s location within a radius of 1,750 feet (minus data relating to utilities). It outlines several crucial rights of consumers, including the rights to:

- Confirm what data is being processed and get access to it.

- Obtain an accessible copy of said personal data (with some notable exceptions).

- Request the controller delete their data.

- Opt out of having their data sold or processed for targeted advertising. However, the law doesn’t give consumers the right to opt out of having their data used for profiling.

Something else the law doesn’t do is give consumers the ability to exercise a private right of action. So, if someone plans to sue under the law regarding violations to their data, then they’re out of luck.

Who the Law Applies To

Something interesting to note is that Iowa’s CDPA is one of the only data privacy laws in the U.S. that doesn’t specify a jurisdictional threshold regarding businesses’ (non-data sale related) annual gross revenues. Rather, it specifies that the law applies to data controllers or processors that conduct business in Iowa or create products or services targeting state residents. Furthermore, applicable organizations also must either control or process the following:

- Personal data of 100,000+ Iowa residents, OR

- Personal data of 25,000+ residents and derives more than 50% of their gross revenue from personal data sales.

As with other U.S. data privacy laws, there are exceptions in terms of businesses that are subject to the law. You can read more about those exceptions in Section 2, 715D.2.

How It Affects Your Business

As per other U.S. data privacy laws, there are certain data privacy and security expectations that data controllers and processors must meet. For example, controllers must respond to consumers’ requests in a reasonable amount of time (“without undue delay”). In this case, you have up to 90 days to respond to consumers’ requests regarding their data rights under the law (with the option of a 45-day extension in some cases). If you deny consumers’ requests to correct, delete, or opt out of sharing/selling their data, then you must provide them with a means to appeal your decision.

The law also affords businesses a 90-day cure period to fix alleged violations; businesses that fail to do so may face injunctions or civil penalties from the state’s attorney general costing upwards of $7,500 per violation. The funds received from such actions are to be placed in a “consumer education and litigation fund.”

8. Montana Consumer Data Privacy Act (MCDPA)

What It Is

The Montana Consumer Data Privacy Act (often cited as MCDPA or MTCDPA) is the state’s new consumer data privacy law that protects consumer rights and outlines the responsibilities of businesses that control or process their data. Formed as Senate Bill 384 (S.B. 384), the act was signed into law on May 19, 2023 by Gov. Greg Gianforte and is set to become effective on Oct. 1, 2024.

What It Does

As with other privacy laws in the U.S., the MCDPA outlines several crucial consumer rights for Montana residents acting in a private (non-commercial or employment) capacity:

- Confirm if their data is being processed by the controller and have access to it.

- Obtain an accessible copy of the consumer’s personal data (with limited exceptions).

- Delete the personal data consumer’s personal data that the controller possesses.

- Opt out of the sale of their data.

Like many of the other U.S. data privacy laws, the Montana law doesn’t provide a private right of action for consumers. Be sure to read the bill’s text to learn more.

Who the Law Applies To

The law applies to entities that do business within the state and handle Montana residents’ personal data. But that’s not all — they also must control or process:

- 50,000+ Montana consumers’ personal data, minus that which is used to complete payment transactions, OR

- 25,000+ Montana consumers’ data and get at least one-quarter of all gross revenue for its sales.

Unlike some other related laws in other states (e.g., Florida, California, etc.), Montana didn’t include any specific financial thresholds for organizations that meet these requirements.

As with all of the other U.S. data privacy and consumer laws discussed in this article, there are exceptions to the rules. The laws don’t apply to many categories of organizations based on their roles and the reasons why they collect and/or process the data.

How It Affects Your Business

In addition to some of the common requirements outlined toward the beginning of the article, processors and controllers have additional responsibilities mentioned in the law. For example, applicable businesses are required to perform and document data protection assessments (DPAs) when selling or processing consumer personal data for profiling or targeting ads.

Montana is one of the U.S. states that requires the establishment of a universal opt-out mechanism, platform, or technology of some kind to allow consumers to put the kibosh on controllers processing their data. Businesses are required to implement this type of opt-out measure by no later than Jan. 1, 2025. But what if their opt-out submission conflicts with their existing privacy settings? Then the opt-out preference takes precedence.

The law states that data controllers have up to 90 days to respond to a consumer’s request for data modifications, deletions, or to opt-out of having their data processed or sold. They also must provide a conspicuous appeals process to consumers and have 60 days to respond once they receive an authenticated appeal request.

If a controller or processor sends Montana consumers’ personal data to another party (i.e., a third-party controller or another processor), they’re not to be held liable for violations conducted by that other party, and vice versa. Basically, it’s a way to hold one party blameless for the violating actions of the other.

Lastly, any violations of the law are enforced by the state’s attorney general. Any violations must be corrected within 60 days of notification; if they don’t, the AG will issue a “notice of violation” and has the right to take action. However, it’s not specified what that action entails or what a maximum damage amount would cost (if anything).

Be sure to read the bill for more detailed information if you do business with Montana residents.

9. Oregon Consumer Data Privacy Act (OCDPA)

What It Is

Oregon Consumer Data Privacy Act (OCDPA) — Senate Bill 619 was signed into law by Gov. Tina Kotek on July 18, 2023. It will become effective July 1, 2024 and, unlike some other states’ similar laws, will apply to most non-profits starting July 1 of the following year.

What It Does

The OCDPA outlines consumer rights that must be exercised via whatever method the controller specifies in their privacy notice. Consumer rights include the ability to request the following:

- Get confirmation about the categories of personal data relating to the consumer that a controller is processing or has processed.

- Update and correct any inaccurate information included in their personal data that the controller has or is processing.

- Demand that the business controlling their personal data must delete it, regardless of whether they gave the information themselves or it was obtained via a third party.

- Require a business to provide a copy of their data in an easily accessible format.

- Opt out of having their information sold or processed for use in targeting ads and profiling.

The law also outlines opt-in requirements for individuals ages 13-15 when it comes to processing their personal data for targeted advertising and profiling or selling it.

Who the Law Applies To

Initially, the law applies to for-profit entities only. This includes persons and businesses that collect or process personal data that identifies (or can reasonably be connected to) an Oregon resident for the purpose of conducting business or producing products/services targeting them. Additionally, they must either control or process:

- 100,000+ Oregon residents’ personal data (minus payment-related transactions), OR

- 25,000+ Oregon residents’ personal data that constitutes more than 25% of its gross revenue sales.

Much like Montana and unlike other states’ laws, Oregon doesn’t specify any financial thresholds for organizations that meet these requirements in their consumer data privacy law. And while it does have exceptions in terms of entities that the law doesn’t apply to (such as government entities and higher education institutions), the law will apply to most non-profit organizations beginning July 1, 2025.

Much like the majority of the laws covered in this article, Oregon’s law doesn’t provide a private right of action for consumers to go after companies for violations. Instead, only the state’s attorney general can take action.

How It Affects Your Business

Businesses that fall under the purview of this law must make it easy to find their privacy notice on their website. They also must provide a means to enable consumers to exercise their rights and revoke previously given consent under the law.

As a data controller, once you receive an authenticated request from a consumer exercising their rights, you have up to 45 days to respond. This applies to correcting, deleting, or making other changes to their processed or sold data. This also includes revoking the data (within 15 days of request receipt). However, when it comes to disclosing which third parties they collected and disclosed the consumers’ personal data to for processing, the controller has the option to specify which third party (or parties) to talk about.

It’s important to note that in Oregon’s law, the “sale” of business includes “the exchange of personal data for monetary or other valuable consideration by the Controller with a third party.” Meaning, if a controller is compensated by other non-monetary means for handing off Oregon consumers’ personal data to a third party, it could constitute a sale of data (with some important exemptions).

Oregon’s AG will notify businesses of violations and provide a 30-day period to cure (fix) the issue. Any violations of the law after that 30-day cure period may result in civil penalties of up to $7,500 per violation. The AG has up to five years to bring an action under sections 1-9 of the act.

10. Tennessee Information Protection Act (TIPA)

What It Is

The Tennessee Information Protection Act (TIPA) — Signed into law by Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee on May 11, 2023, the law is set to kick into effect July 1, 2025. (It was originally set to take effect July 1, 2025, but the date was amended in May 2023.)

This law appears to be more favorably aligned with businesses’ interests than with consumers’ when compared to some other U.S. data privacy laws (such as California’s CCPA with its CPRA amendment).

What It Does

TIPA outlines several crucial rights of consumers that protect their personal, non-deidentified or publicly available data when acting as private individuals (not as employees or in other contexts):

- Confirm what info the controller is processing, what categories of data it’s sold, and what categories of third-party organizations the data has been sold to.

- Ensure they have access to the data.

- Get a portable copy of the data held by the controller that the consumer can use to transmit to another controller.

- Make any corrections necessary to amend inaccuracies with specific considerations.

- Request the controller delete their identifiable personal data.

Much like many others, the Tennessee law doesn’t give consumers a private right of action or the ability to launch a class action lawsuit for violations. However, “appropriate relief may be awarded to each identified consumers affected by this regulation, regardless of whether actual damages were suffered” and the court reserves the right to award treble damages.

Who the Law Applies To

The law applies to businesses and individuals who do provide products and services targeting state residents and meet one of the following conditions:

- Control or process personal data relating to 100,000+ consumers within a calendar year, OR

- Control or process personal data of 25,000+ consumers and get >50% of their gross revenue by selling it.

However, much like many other states’ laws, some entities are exempt based on their roles, legislative authority, and other considerations. Read more about the law to explore those entities.

How It Affects Your Business

The law outlines specific requirements for businesses regarding data security standards and protections for identifiable data. It also imposes obligations about clearly disclosing how and why the information is needed, along with how it’ll be used and who the information is shared with. It also requires businesses to provide an appeals process to consumers who wish to appeal a business’s decision to deny their request to exercise their rights.

Want some good news? Businesses that maintain a written privacy program that “reasonably conforms to” the latest version of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) privacy framework get to enjoy an “affirmative defense.” (A bit of a “safe harbor,” if you will.) This means that if there’s a violation, as long as they comply with said written policy, a controller or processor may potentially avoid issues relating to TIPA violations.

TIPA also provides a 60-day cure period and has no sunset date as of the time of writing this article. However, for uncured violations, injunctive relief, declaratory judgment, or a civil penalty (of up to $15,000 per violation) may apply depending on the situation. However, the quasi “safe harbor” we mentioned earlier may mean that you may have some protection as well if you fail to cure within that 60-day period.

11. Texas Data Privacy and Security Act (TDSPA)

What It Is

Texas Data Privacy and Security Act (TDPSA) — The Lone Star’s Governor, Greg Abbott, signed the data privacy bill into law (HB-4) on June 18 2023. It’s set to go into effect July 1, 2024. A specific portion (Chapter 541, Business & Commerce Code) won’t be effective until the following year.

What It Does

The TDPSA gives consumers a way to exercise limited control over their data in terms of how it can be accessed, processed, sold, or used. It outlines several crucial rights of consumers, such as the ability to:

- Confirm whether their personal data is being processed and that they have access to it.

- Delete personal data that’s been collected on the consumer.

- Gain access to their personal data in a portable, accessible format.

- Opt out of having their data processed for sale, profiling, or targeted advertising.

As with most of other data privacy law in the U.S., the TDPSA doesn’t give consumers a private right of action in response to violations.

Who the Law Applies To

The law applies to individuals and businesses who meet the following criteria:

- Provide products and services aimed at Texas residents.

- Process or engage in selling residents’ personal data.

- Is not a small business (unless they have specific consent from the consumer)

It doesn’t set revenue restrictions or qualifiers like some other U.S. data privacy laws do in other states.

Some types of entities and organizations are exempt based on certain factors such as their roles and responsibilities, as well as other interacting laws and regulations. We won’t get into all of that here, but you can read more about the law to explore those types of entities in bill’s text.

How It Affects Your Business

The law outlines key considerations and requirements that business controllers and processors must implement and adhere to. For example, section 541.104 outlines that data processors and controllers must have a contractual relationship that spells out key specifications.

The TDPSA requires businesses that meet the law’s data collector requirements to:

- Gain clear, unambiguous consent from the consumer regarding the processing and use of their personal data.

- Provide a mechanism on their websites for consumers to submit their requests to exercise their rights.

- Recognize opt-out preference indicators starting Jan. 1, 2025.

- Provide specific disclosures when engaging in the sale of Texas consumers’ biometric or otherwise personal data.

Unlike pretty much all of the other data security laws we’ve read, Texas’ specifies the precise language to use for those notices, e.g.

- “NOTICE: We may sell your sensitive personal data.”

- “NOTICE: We may sell your biometric personal data.”

Controllers are required to carry out and document a confidential data protection assessment regarding sale and processing activities relating to personal data. For specifics on these requirements, read the law in full.

Enforcement of any violations is up to the state’s attorney general. Failures to comply with the requirements by the 30-day cure period (and for new violations thereafter) may result in a civil penalty of up to $7,500 per violation. The attorney general also may seek injunctive relief if necessary.

12. Utah Consumer Privacy Act (UCPA)

What It Is

Utah Consumer Privacy Act (UCPA) — Utah will close out the year 2023 with their new data privacy law, which took effect Dec. 31, 2023. It was signed into law by Utah Governor Spencer J. Cox on March 24, 2022.

What It Does

The UCPA outlines some crucial rights of consumers that they can exercise:

- Confirm if a controller is processing their data and that the consumer has access to that information.

- Reserve the right to delete their personal data that the consumer provided to the controller.

- Access their data through means that are portable, accessible, and transmittable.

- Opt out of having their data processed for sale and targeted advertising.

However, it doesn’t offer any recourse in terms of a private right of action. As a consumer, you also can’t opt out of having your data used for profiling or even make any corrections to inaccurate information.

Who the Law Applies To

The law applies to any controller and processor who:

- Does business within the state of Utah.

- Provides products or services targeting Utah residents.

- Has $25 million+ in annual revenue.

- Meets one of the following thresholds:

- Processes personal data of 100,000+ consumers, OR

- Gets >50% of its gross revenue from sale of data and controls or processes the data of 25,000 consumers.

As with virtually every other U.S. data privacy law, there are always exceptions to the rule. Some examples of entities that the law doesn’t apply to include government institutions and contractors, non-profits, higher education institutions, and a bunch of others outlined in the bill. Of course, there are also plenty of specific categories of activities that don’t fall under the law. Read more about all of those exceptions in the bill.

How It Affects Your Business

As a data controller, your job is to inform consumers about your data collection activities and provide the means to exercise their rights under the law. Part of this involves providing consumers with a “reasonably accessible and clear privacy notice” that informs them about pertinent info regarding what’s being collected and how it’s being used.

You must respond to authenticated consumer requests within 45 days of request receipt. However, you have the option of extending that period by another 45 days, if need be, but you must inform the consumer about the extension.

However, unlike other states’ similar laws, Utah’s doesn’t require data controllers to provide an appeals process for consumers whose requests are denied.

For businesses that violate the law, there’s a 30-day cure period from when they receive a violation notice from the state’s attorney general. If they fail to cure within the prescribed time, they may be fined up to $7,500 per violation. The funds just go into a fund that’s used for investigations, attorney fees, consumer education, etc. If the fund exceeds $4 million at the end of the fiscal year, the money is then transferred into the state’s General Fund.

13. Virginia Consumer Data Privacy Act (CDPA)

What It Is

The Virginia Consumer Data Privacy Act (CDPA, sometimes called the VACDPA) was signed by Gov. Ralph Northam on March 2, 2021. The law, which took effect Jan. 1, 2023, was the second such comprehensive consumer data privacy law that was launched by a state (following California’s CCPA).

What It Does

The CDPA affords consumers with several critical rights when it comes to the privacy and usage of their personal data:

- Confirm whether a controller is processing their data and that the consumer has access to it.

- Correct inaccuracies within the data.

- Obtain a copy of their data in a readily accessible format.

- Opt out of having their data being sold or processed for:

- Targeted advertising

- Profiling

- Delete any data that they (or someone else) provided about the consumer.

Unsurprisingly, the law doesn’t provide a private right of action for consumers whose rights are violated.

Who the Law Applies To

The law applies to any individuals who conduct business within the Commonwealth of Virginia or who provides products/services targeting residents during a calendar and meet one of the following criteria:

- Control or process 100,000+ consumers’ personal date, OR

- Control or process the personal data of 25,000+ consumers AND get <50% of their cross revenue from its sales.

As far as exempt entities go, they’re the usual gang — government entities, financial institutions, nonprofits, higher education institutions, etc. Unsurprisingly, data used for a litany of specified purposes and use cases also would be exempt from this law.

How It Affects Your Business

Applicable businesses must get the consumer’s content. They also must comply with an authenticated consumer’s request to exercise their rights. Although businesses are expected to reply without undue delay, they technically have up to 45 days of receipt of an authenticated consumer request to respond.

If the decision is to deny their request, you must inform the consumer within that period and provide a justification for why and info on how to file an appeal. An appeal decision must be communicated to the consumer within 60 days of receipt of the appeal request. Appeal denials also must include information about how the consumer may submit a formal online complaint to the Attorney General.

Data controllers must establish a contract with processors that governs their actions regarding the personal data they handle. They’re also required to “conduct and document a data protection assessment” regarding how personal data is processed for sale, targeted advertising, and profiling, any activities that could increase potential harm.

Any violations of the law can result in the attorney general launching a civil investigation. There’s a 30-day cure period for businesses to fix the violation. If the violation extends beyond that period, the AG may seek injunctive action or civil penalties upwards of $7,500 per violation. (Any penalties recovered go into the state’s Regulatory, Consumer Advocacy, Litigation, and Enforcement Revolving Trust Fund.)

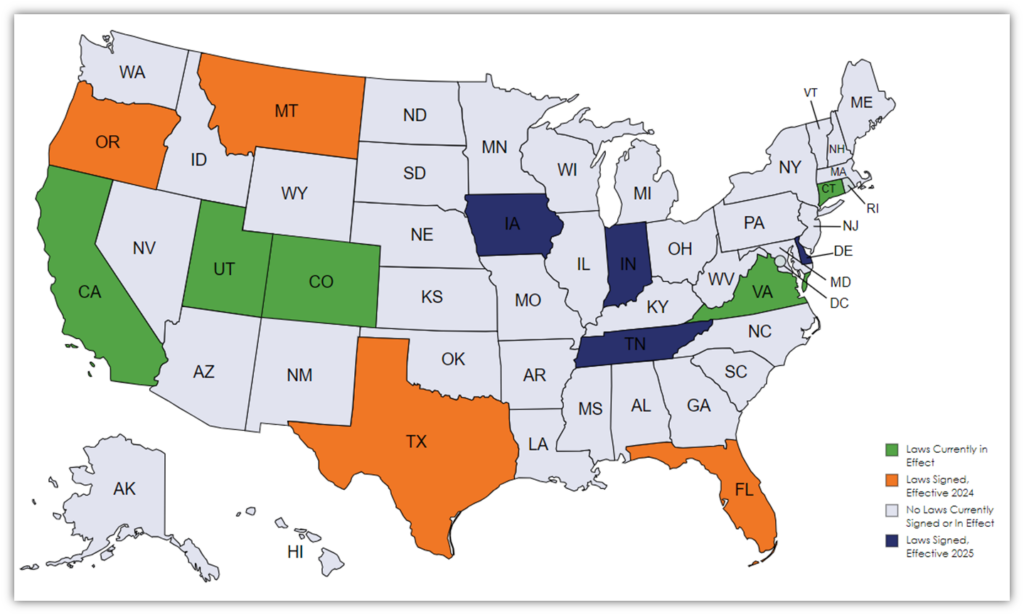

How Soon Can We Expect to See These Laws in Effect?

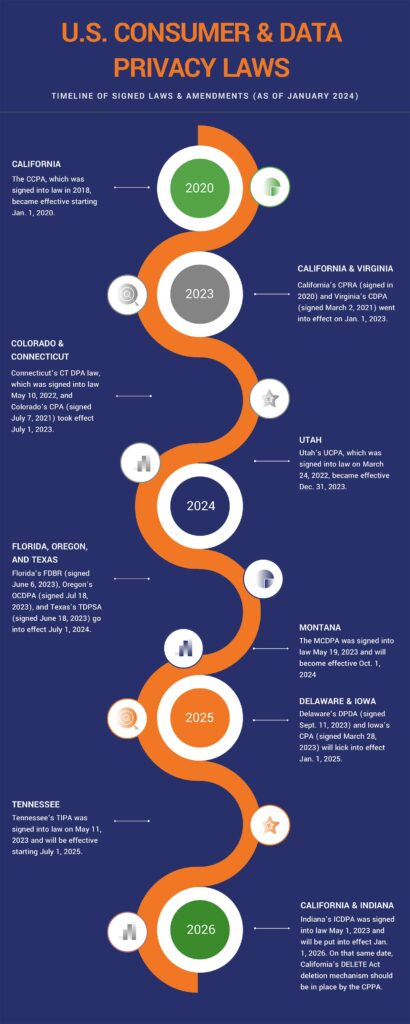

That’s a good question. There isn’t one date when all of these laws will roll out; rather, some laws are already in effect while others will roll out over the next couple of years. Here’s a quick overview of what this looks like in a timeline:

Final Thoughts on Data Privacy Laws in the U.S.

We’re living in interesting times. We live in a world where information is virtually at our fingertips; and that includes sensitive, personally identifiable information. And when it comes to drawing a line between the rights of U.S. consumers and the desires and needs of businesses to use that data, it’s nothing short of a battleground.

There’s plenty to know about the specifics of each law, if you have the free time (and attention span) to dedicate to learning more about them. However, we understand that most of our readers are too busy to do that, so we hope you’ve found this article useful and informative.

Of course, the laws covered in this article aren’t the only U.S. laws that have been proposed considered at some point. There are other states that have proposed legislation that have stalled, failed, or are currently under consideration — New York, Illinois, South Carolina, Ohio, just to name a few. And we’ll keep our eyes out for any movement with regard to new data and consumer privacy laws that may result.

![A Look at 30 Key Cyber Crime Statistics [2023 Data Update]](https://www.thesslstore.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/cyber-crime-statistics-feature2-75x94.jpg)

Be the first to comment