Google sees 45% dip in news traffic thanks to Article 11 of the EU Copyright Directive

Snippet-less search results make people less likely to engage with news media

Google has its hands full right now in Europe. In addition to the recent $57-million fine levied against it by France’s CNIL, it’s also trying to combat new legislation connected with the EU Copyright Directive.

This is an interesting case because it illustrates the different legislative and judicial perspectives that dominate the discourse on either side of the pond. It also looks like it could have major social impacts across Europe.

So today, we’re going to delve into Articles 11 and 13 of the EU Copyright directive, Google’s position and what a 45% decline in news traffic potentially hearkens.

Let’s hash it out.

The EU Copyright Directive – Solid idea, bad execution

As we’ve covered many times, the way Europe views individual rights vs. corporate rights and the way that the US views them couldn’t be more opposed. Whereas in the US, corporations are afforded all the same rights as individuals and Google’s search results have been ruled “protected speech,” in Europe there is far more impetus on protecting the rights and privacy of the individual.

While it might not seem that way at first blush, the copyright directive is more of the same. It’s focused on protecting the rights of artists and content creators, like photographers, writers, etc.

Specifically, article 11 of the EU Copyright Directive has derisively been nicknamed the “Link tax,” which forces news aggregator sites and search engines to pay licensing fees for displaying article snippets.

The intention behind this is to ensure that the creator of a piece of content sees their share of the revenue from it. That’s a noble goal. I feel uniquely qualified to say that, especially as a former reporter that saw more than a few scoops pilfered by bloggers and other publications that couldn’t even bother to credit the source, let alone ensure I was being fairly compensated for the work I’d done.

But the Copyright Directive, as it’s currently written, doesn’t accomplish that effectively, either. In its earnest attempt to protect the rights of content creators it’s going to end up knee-capping them. Again, speaking from my own experience, sites like Google drive far more traffic to a piece of content than it steals. Google, and similar sites and services, shouldn’t be punished for amplifying content.

Google is right about this one

Now, a couple of things. Anyone that reads this blog regularly knows I don’t pull any punches when it comes to Google. I’ve criticized it more than a few times. But in this case, Google is absolutely correct.

Here’s a practical example, I wrote for a top-15 US paper, the Miami Herald, but direct traffic to our website wasn’t its biggest source. Search was. It was because our articles surfaced at the top of so many search results in Google news.

Google news didn’t hinder our traffic or profits at all, it amplified them.

Already, Google has threatened to shutdown its Google News service in Europe over this regulation.

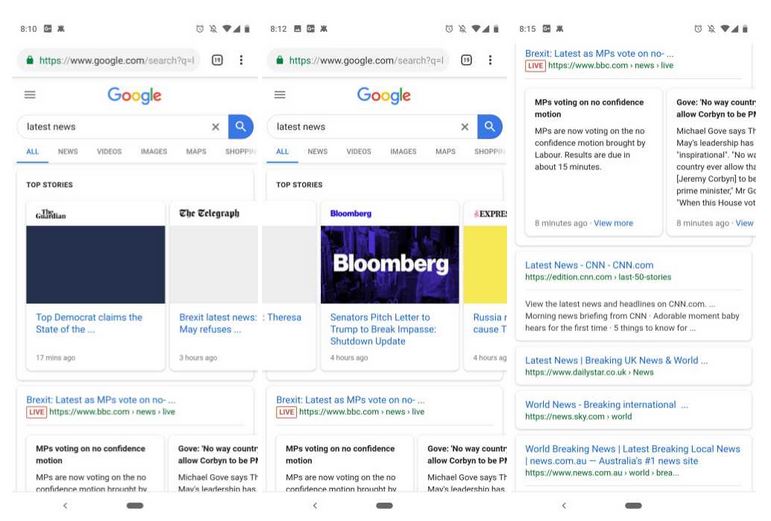

Now, in a blog post published on Thursday, Google is backing its threat with data. After testing new Copyright Directive-compliant search results it saw a 45% drop in news traffic.

We reiterate our commitment to supporting high-quality journalism. However, the recent debate shows that there’s a fundamental misunderstanding of the value of headlines and snippets—very short previews of what someone will find when he or she clicks a link. Reducing the length of the snippets to just a few individual words or short extracts will make it harder for consumers to discover news content and reduce overall traffic to news publishers.

Let me illustrate this with an example. Every year, we run thousands of experiments in Search. We recently ran one in the EU to understand the impact of the proposed Article 11 if we could show only URLs, very short fragments of headlines, and no preview images. All versions of the experiment resulted in substantial traffic loss to news publishers.

Even a moderate version of the experiment (where we showed the publication title, URL, and video thumbnails) led to a 45 percent reduction in traffic to news publishers. Our experiment demonstrated that many users turned instead to non-news sites, social media platforms, and online video sites—another unintended consequence of legislation that aims to support high-quality journalism. Searches on Google even increased as users sought alternate ways to find information.

Here’s a screenshot from 9to5Google showing the split test, as you can see the Copyright Directive-compliant snippet now looks a lot like how Google SERPs display tweets.

This is definitely not what the EU intended with the copyright directive: a massive reduction in its citizens’ interaction with the news. Maligned though Google may be, its market share yields it considerable influence. Google is the search engine of record for much of the western world. So much so that Google has become a verb for searching the internet. If you’re seeing a 45% decrease in news traffic on Google, that’s a significant portion of the population that’s no longer clicking on news stories.

We are not at a point in the world where people should be paying LESS attention.

A quick word about Article 13

Article 13 is arguably the most alien part of the copyright directive for Americans and American companies. That’s because in the US we are guided by Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act that offers companies and platforms immunity from prosecution for any illicit or illegal content posted by third parties.

That’s why someone like Alex Jones can thrive on Twitter and Facebook for years – they’re not liable for what he puts on their platforms.

That doesn’t fly in the EU, and article 13 is why, it holds the platforms hosting pirated or illegal content responsible for said content.

Per Google:

Companies that act reasonably in helping rights holders identify and control the use of their content shouldn’t be held liable for anything a user uploads, any more than a telephone company should be liable for the content of conversations. We are committed to protecting content, but we need rights holders to cooperate in that process. The final text should make it clear that rights holders need to provide reference files of content, and copyright notices with key information (like URLs), so that platforms can identify and remove infringing content.

How this all ends up ultimately depends on whether or not the EU parliament and its other governing bodies can come to some kind of a compromise on the wording. Unfortunately, much like with the GDPR and other like-minded legislation, there doesn’t always seem to be a lot of attention paid to some of the more unforeseen consequences that can emerge from something like this.

Either way, the way it’s written right now portends disaster.

As always, leave any comments or questions below…

![A Look at 30 Key Cyber Crime Statistics [2023 Data Update]](https://www.thesslstore.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/cyber-crime-statistics-feature2-75x94.jpg)

5 Ways to Determine if a Website is Fake, Fraudulent, or a Scam – 2018

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityHow to Fix ‘ERR_SSL_PROTOCOL_ERROR’ on Google Chrome

in Everything EncryptionRe-Hashed: How to Fix SSL Connection Errors on Android Phones

in Everything EncryptionCloud Security: 5 Serious Emerging Cloud Computing Threats to Avoid

in ssl certificatesThis is what happens when your SSL certificate expires

in Everything EncryptionRe-Hashed: Troubleshoot Firefox’s “Performing TLS Handshake” Message

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityReport it Right: AMCA got hacked – Not Quest and LabCorp

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityRe-Hashed: How to clear HSTS settings in Chrome and Firefox

in Everything EncryptionRe-Hashed: The Difference Between SHA-1, SHA-2 and SHA-256 Hash Algorithms

in Everything EncryptionThe Difference Between Root Certificates and Intermediate Certificates

in Everything EncryptionThe difference between Encryption, Hashing and Salting

in Everything EncryptionRe-Hashed: How To Disable Firefox Insecure Password Warnings

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityCipher Suites: Ciphers, Algorithms and Negotiating Security Settings

in Everything EncryptionThe Ultimate Hacker Movies List for December 2020

in Hashing Out Cyber Security Monthly DigestAnatomy of a Scam: Work from home for Amazon

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityThe Top 9 Cyber Security Threats That Will Ruin Your Day

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityHow strong is 256-bit Encryption?

in Everything EncryptionRe-Hashed: How to Trust Manually Installed Root Certificates in iOS 10.3

in Everything EncryptionHow to View SSL Certificate Details in Chrome 56

in Industry LowdownPayPal Phishing Certificates Far More Prevalent Than Previously Thought

in Industry Lowdown