We still need more proof that the DV SSL Visual Indicator is too strong?

This is why we can’t have nice things.

Over the weekend, news surfaced that a researcher had found a fake website purporting to be a Symantec blog. Of course, it wasn’t. It was secretly spreading a new variant of OSX.Proton password stealer.

The malware family has been circulating for a while since its initial appearance in March 2017 and has since been distributed via a compromised Handbrake application and a similar compromise of the Ellmedia Software applications, according to a Nov. 20, 2017, Malwarebytes blog post.

The website was convincing, too. As is commonplace, these phishers – phishermen? phisherpeople? is there any consensus on this? Anyway, as is commonplace, the website perfectly mimicked the look and feel of an authentic Symantec property. They even used the real name and address of another Symantec site in the domain registration information.

Where things broke down was with the email address that was used in the registration, the same one that was used to register the DV SSL certificate it was using, in this case from Comodo. Obviously, Symantec wouldn’t be using a Comodo SSL certificate on any of its sites. And while I can’t see the certificate information myself, I’d be willing to wager this was likely a free DV offering from Comodo via its AutoSSL cPanel deal.

Regardless, this just underscores a point we have been making organizationally, along with others throughout the industry: the current visual indicator for DV SSL is just too strong.

How did we get here?

Encryption is becoming mandatory. That’s the short answer. Google, and eventually Mozilla, are helping to facilitate this seismic shift from HTTP to HTTPS by changing their browser UI so that it says “Secure” anytime SSL is present.

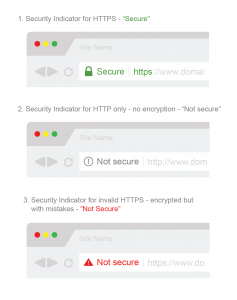

Let me say that another way. Although I believe their stated intention is eventually to remove the “Secure” indicator, entirely – for now there exists a binary. A website either has an SSL certificate installed and is making secure HTTPS connections, in which case it says “Secure” in the address bar. Or, a website doesn’t have SSL, in which case it isn’t making encrypted HTTPS connections. In that case, the site is marked either “Not Secure” or given some less extreme version of the warning.

Let me say that another way. Although I believe their stated intention is eventually to remove the “Secure” indicator, entirely – for now there exists a binary. A website either has an SSL certificate installed and is making secure HTTPS connections, in which case it says “Secure” in the address bar. Or, a website doesn’t have SSL, in which case it isn’t making encrypted HTTPS connections. In that case, the site is marked either “Not Secure” or given some less extreme version of the warning.

The problem with this is that we, as an industry – browsers, CAs, everyone – have done a poor job educating users what the browser UI is intended for and what it actually communicates.

For instance, Secure ≠ Safe.

Now, this would seem really nit-picky if not for the fact that, in the interest of wide-scale adoption for SSL encryption, we’ve basically created a free-tier of DV certificate. You can get free DV SSL certificates from Amazon, Let’s Encrypt, Comodo/cPanel – hell, our parent company, The SSL Store™ even has a program in conjunction with Symantec – the point is they’re commonplace.

And that’s great. There shouldn’t be an economic gatekeeper between the internet and basic SSL.

The problem is that we’ve created a situation where a well-intentioned security product can actually aid cybercriminals in defrauding consumers.

Now, before I go any further, I’m not saying:

- Free SSL is bad

- We should get rid of Free SSL

- Free SSL is the cause of this problem

I’m not saying any of those things. Nor is this argument based out of some sort of economic desperation caused by Let’s Encrypt and its ilk. It has nothing to do with any of these things.

It’s just common sense.

It Should Not Say “Secure” for DV SSL

Like I said earlier, I think this is where Google and Mozilla are eventually planning to take this, but let’s turn the visual indicator for DV SSL neutral. Everyone wants encryption to become a baseline security standard, so let’s start treating it like one. If you don’t have SSL you get a negative, “Not Secure” indicator. DV SSL activates a neutral indicator, like a simple padlock icon.

And then if you want to keep Secure you can use it for OV, which requires a greater degree of validation to obtain. The point really isn’t to litigate the latter half of the chart. Not right now. We can continue to agree to disagree on OV and EV UI for a while longer.

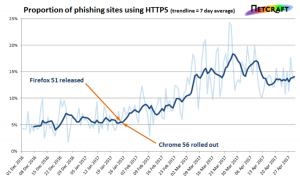

But in the interim, let’s tamp down on something that has become an increasingly effective tactic in phishing: getting your website marked secure.

But in the interim, let’s tamp down on something that has become an increasingly effective tactic in phishing: getting your website marked secure.

Not to double back to the argument over OV/EV UI again, but one of the most common arguments against giving OV its own UI is that, to the browsers, it’s not secure enough. Yet, at the same time, we’re willing to slap a “Secure” label on any website that can obtain free SSL? It seems like it’s kind of talking out of both sides of the mouth.

Regardless, the point I’m making is that we need to change the visual indicators for DV SSL. It’s causing enough friction in other places that it needs to be discussed. And no, maybe anecdotal evidence about a security giant being spoofed isn’t what you’re looking for, but it’s hard to ignore the studies that show a decided increase in SSL encrypted phishing scams.

It’s an easy fix. One that makes the internet safer.

So what are we waiting for?

![A Look at 30 Key Cyber Crime Statistics [2023 Data Update]](https://www.thesslstore.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/cyber-crime-statistics-feature2-75x94.jpg)

5 Ways to Determine if a Website is Fake, Fraudulent, or a Scam – 2018

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityHow to Fix ‘ERR_SSL_PROTOCOL_ERROR’ on Google Chrome

in Everything EncryptionRe-Hashed: How to Fix SSL Connection Errors on Android Phones

in Everything EncryptionCloud Security: 5 Serious Emerging Cloud Computing Threats to Avoid

in ssl certificatesThis is what happens when your SSL certificate expires

in Everything EncryptionRe-Hashed: Troubleshoot Firefox’s “Performing TLS Handshake” Message

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityReport it Right: AMCA got hacked – Not Quest and LabCorp

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityRe-Hashed: How to clear HSTS settings in Chrome and Firefox

in Everything EncryptionRe-Hashed: The Difference Between SHA-1, SHA-2 and SHA-256 Hash Algorithms

in Everything EncryptionThe Difference Between Root Certificates and Intermediate Certificates

in Everything EncryptionThe difference between Encryption, Hashing and Salting

in Everything EncryptionRe-Hashed: How To Disable Firefox Insecure Password Warnings

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityCipher Suites: Ciphers, Algorithms and Negotiating Security Settings

in Everything EncryptionThe Ultimate Hacker Movies List for December 2020

in Hashing Out Cyber Security Monthly DigestAnatomy of a Scam: Work from home for Amazon

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityThe Top 9 Cyber Security Threats That Will Ruin Your Day

in Hashing Out Cyber SecurityHow strong is 256-bit Encryption?

in Everything EncryptionRe-Hashed: How to Trust Manually Installed Root Certificates in iOS 10.3

in Everything EncryptionHow to View SSL Certificate Details in Chrome 56

in Industry LowdownPayPal Phishing Certificates Far More Prevalent Than Previously Thought

in Industry Lowdown